100 years of the Photographic Department: Part One

A history

The Photographic Department started life as a team of three in 1919. Their original function was to photograph the collection for record and to produce prints and cards for sale. By 1939, this work had expanded to record the cleaning of pictures.

The war years

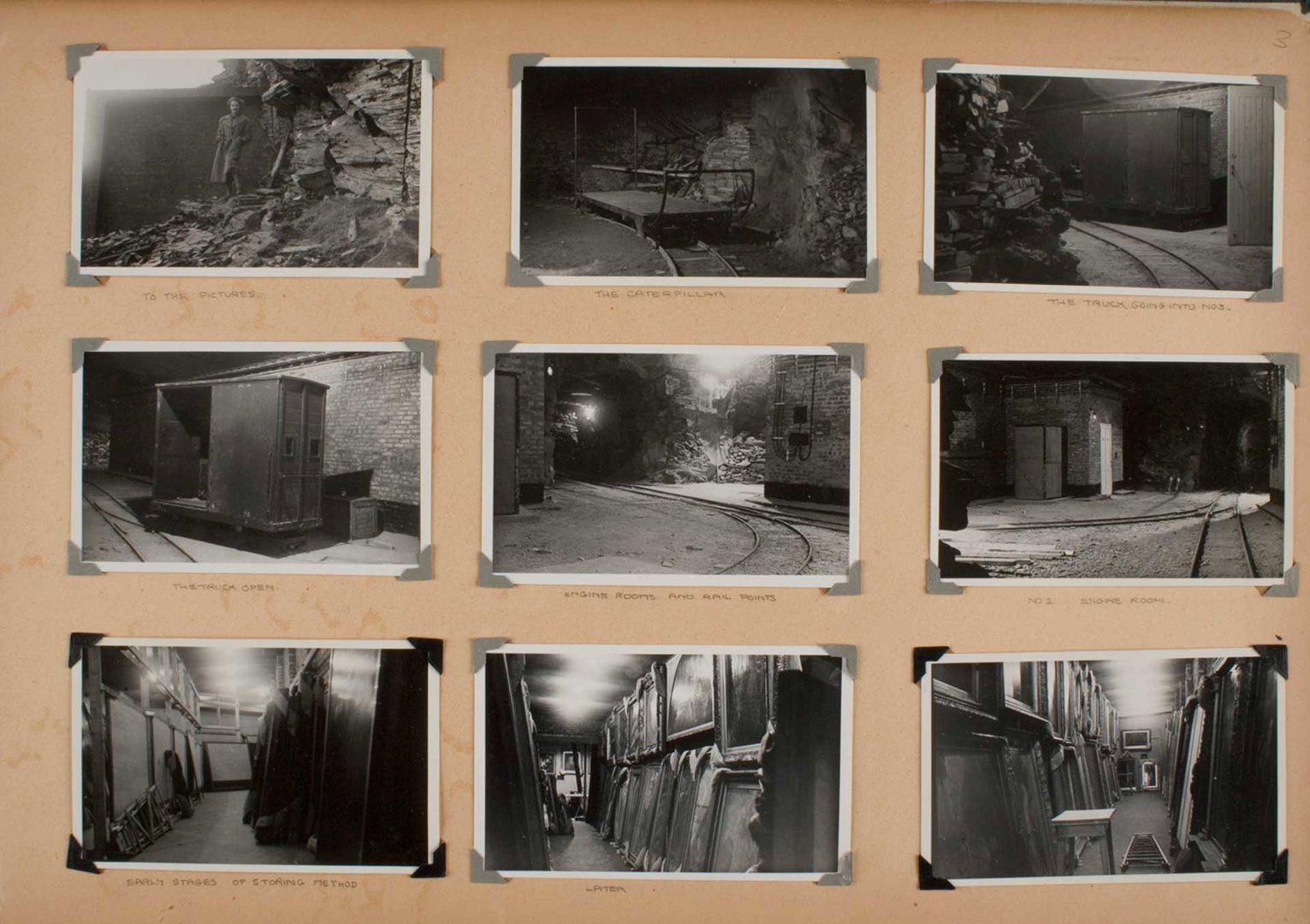

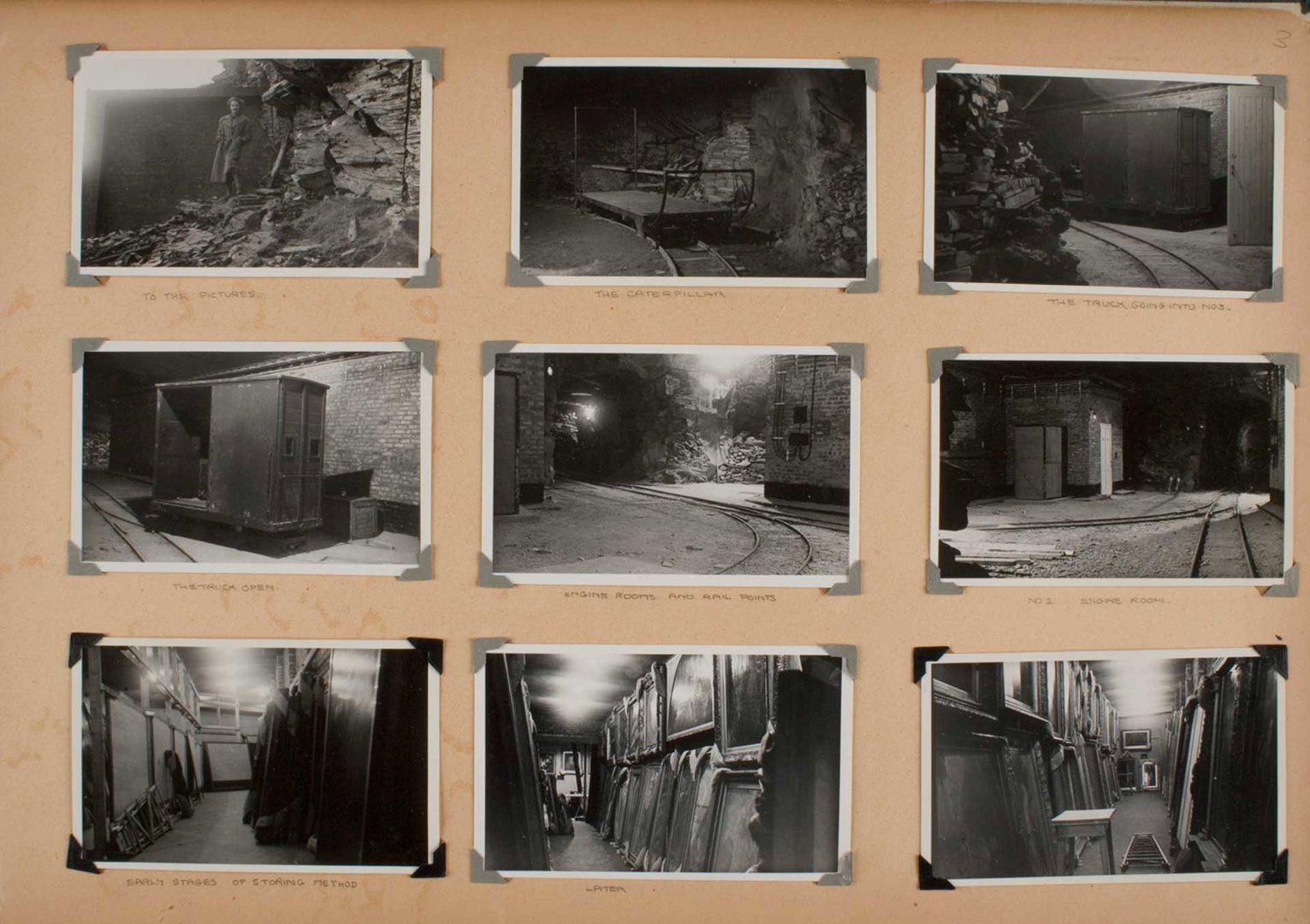

During the Second World War the staff was reduced to two, and when the Gallery’s collection was moved out of Blitz-struck London to a disused slate mine in Wales, a photographic studio and dark room was set up in the mine.

After the war, the department grew to support the work of the newly established Conservation Department and took over X-radiography from the Scientific Department who had been producing X-Rays since the 1930s.

The digital years

1993 saw the construction of the first secure, environmentally controlled and monitored Photographic Archive. It contains the Gallery’s photographs from establishment to the present day, providing a historical record of the collection, people, and building. The archive was relocated to its current site in 2003:

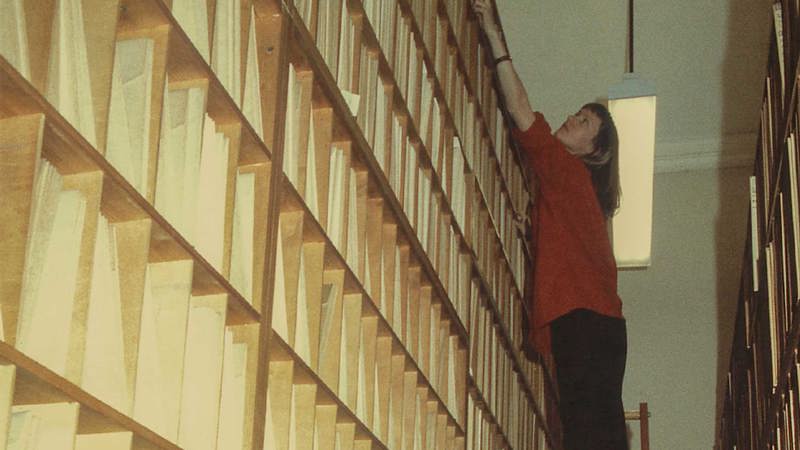

Large format negatives in the old Negative Store

The Photographic Archive as it looks today

Large format negatives in the old Negative Store

The Photographic Archive as it looks today

During the mid-1990s, when digital photography was in its infancy, the Gallery embarked on the ground-breaking MARC (Methodology for Art Reproduction in Colour) project, funded through a European Community research scheme, to develop a digital camera capable of making high resolution images of our paintings. Using a second version of this camera, capable of producing final colour images with a resolution of c.10000 x 10000 pixels, our entire collection was photographed and digitised over a period of 18 months starting in 2000.

Photographing the collection

Technology may have changed over the years but the need to photograph the collection has stayed the same:

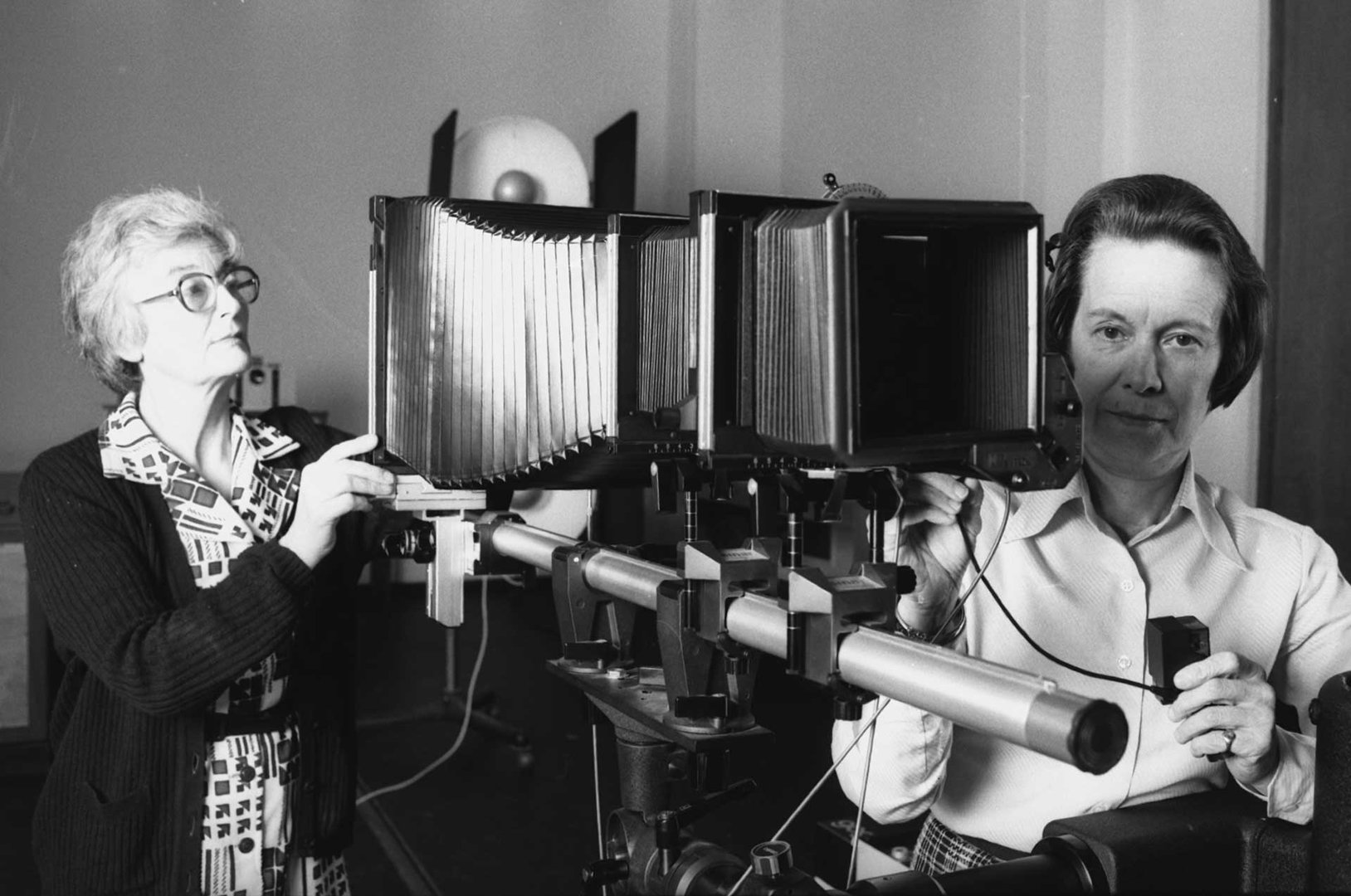

In the early years, paintings were photographed using a wooden plate camera. The large format glass negatives are preserved in the Photographic Archive.

Glass negatives were replaced by film: black and white negatives and colour transparencies.

This image from 2000 shows Monet’s 'Bathers at La Grenouillère' being photographed on a digital camera during the MARC project.

Today we use a Hasselblad medium format digital camera and a micro positioning easel, which slowly moves the painting in front of the camera so we can take multiple photographs at 600dpi which are then stitched together to make an ultra high resolution composite image.

This image from 'The Wilton Diptych' (being photographed in the previous image) shows the level of detail possible using this technique.

In the early years, paintings were photographed using a wooden plate camera. The large format glass negatives are preserved in the Photographic Archive.

Glass negatives were replaced by film: black and white negatives and colour transparencies.

This image from 2000 shows Monet’s 'Bathers at La Grenouillère' being photographed on a digital camera during the MARC project.

Today we use a Hasselblad medium format digital camera and a micro positioning easel, which slowly moves the painting in front of the camera so we can take multiple photographs at 600dpi which are then stitched together to make an ultra high resolution composite image.

This image from 'The Wilton Diptych' (being photographed in the previous image) shows the level of detail possible using this technique.

Technical photography

A large part of the department's remit involves technical imaging to support research undertaken by curatorial, scientific and conservation teams.

Different forms of technical imaging can reveal aspects about paintings not always visible to the human eye, for example:

X-ray

X-ray imaging can be used to see beneath the surface of a painting, often revealing changes that may have occurred at different stages of its development. This x-ray revealed an entirely different portrait lying beneath Goya’s ‘Doña Isabel de Porcel’.

Ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence

This UV image of Artemisia Gentileschi’s ‘Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria’, taken during its restoration, shows how an aged natural resin coating (visible on the right half of the painting, and removed on the left half) displays a characteristic greenish fluorescence under UV. You can also see historic retouching from earlier restoration, which shows up as dark patches (rather generously applied over old damages), in the background to the right of the figure, for example.

Raking light

Raking light is a technique in which a painting is illuminated from one side only, at an oblique angle in relation to its surface. It reveals a painting’s surface texture, such as in this image of Crivelli’s ‘Saint Stephen’. We use raking light to judge aspects of the condition of a painting.

Documenting conservation

We also use photography to document every stage of a painting’s conservation treatment. This image of ‘The Adoration of the Shepherds’ by an unknown Florentine artist shows the painting half-way through a treatment to remove discoloured, aged varnish.

X-ray

X-ray imaging can be used to see beneath the surface of a painting, often revealing changes that may have occurred at different stages of its development. This x-ray revealed an entirely different portrait lying beneath Goya’s ‘Doña Isabel de Porcel’.

Ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence

This UV image of Artemisia Gentileschi’s ‘Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria’, taken during its restoration, shows how an aged natural resin coating (visible on the right half of the painting, and removed on the left half) displays a characteristic greenish fluorescence under UV. You can also see historic retouching from earlier restoration, which shows up as dark patches (rather generously applied over old damages), in the background to the right of the figure, for example.

Raking light

Raking light is a technique in which a painting is illuminated from one side only, at an oblique angle in relation to its surface. It reveals a painting’s surface texture, such as in this image of Crivelli’s ‘Saint Stephen’. We use raking light to judge aspects of the condition of a painting.

Documenting conservation

We also use photography to document every stage of a painting’s conservation treatment. This image of ‘The Adoration of the Shepherds’ by an unknown Florentine artist shows the painting half-way through a treatment to remove discoloured, aged varnish.

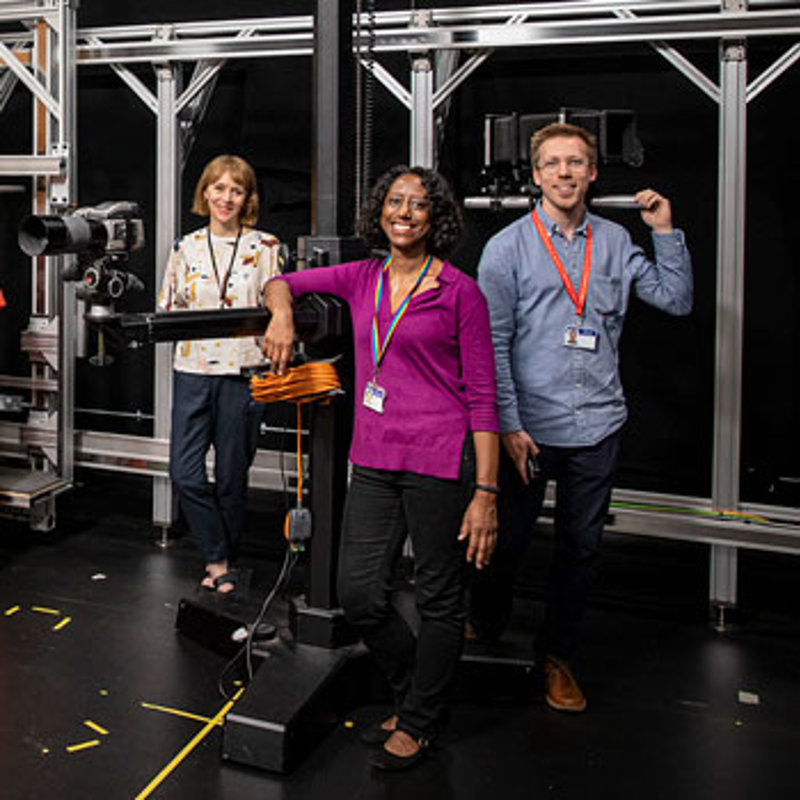

The department today

Now a team of eight, we continue to work at the highest level of cultural heritage photography, providing high quality, colour managed images worthy of the masterpieces in our collection.