In detail: Saint Michael Triumphs over the Devil

Bermejo's masterpiece, 'Saint Michael Triumphs over the Devil', is widely considered the most important early Spanish painting in Britain.

It portrays Saint Michael defeating the devil, a scene taken from the Book of Revelation which became a popular subject in art from the Middle Ages onwards.

Bermejo's earliest documented painting; it is a tall panel, roughly six feet high, and painted in astonishing detail. Recently restored, the painting reveals the extent of Bermejo's technical skill and mastery of the oil painting technique that had been perfected in the Netherlands.

Discover some of the details in the painting, and click to expand:

Saint Michael was an Archangel, the highest order of angels. Bermejo conveys his heavenly qualities: his graceful, feathered wings and billowing cloak fill the canvas and give the slender saint a volume and presence that he would not otherwise have. His face is idealised – he has a serene expression, without a trace of effort or fear.

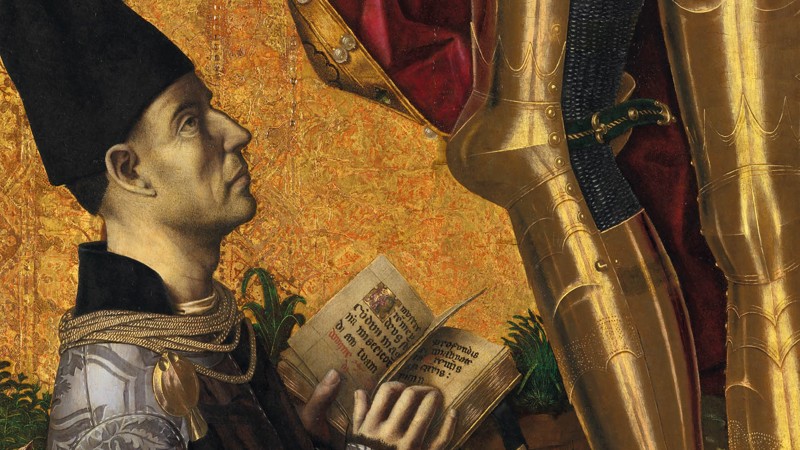

In contrast, the donor, Antoni Joan (who commissioned and financed the painting) has a naturalistic face. Here is a real man with wrinkles, stubble and a distinctive kink in his nose. It is clear that he and Saint Michael are from different worlds. Joan's sword and heavy chains indicate that he is a knight, and he holds open a book of Psalms.

The devil is made up of a combination of animals. Devils were often shown with more than one face, inspired by the description in the Bible of a seven-headed dragon. His torso is formed of a second face, and live snakes slither out of the gaping mouth in his stomach. There are reptilian heads at his elbows and at the joints of his bird-like back legs. His crocodile-like tail, which ends in a single claw, is wrapped around Saint Michael’s calf.

Saint Michael is dressed in an exquisite suit of tournament armour, made of gold and set with huge jewels, including lines of large pearls at the wrists and ankles.

The saint's breastplate reflects the towers of the holy city of Jerusalem as described in the Book of Revelation. The reflection also helps to give the impression of the armour's lustre.

He holds a small shield or buckler in his left hand. Bucklers always had a dome-shaped centre to help them deflect blows. Saint Michael's is particularly unusual – and fantastical – since it appears to be made of rock crystal. As with his armour, it is set with pearls.

Saint Michael’s resplendent cloak of cloth gold and red lining takes up much of the canvas and is painted in incredible detail. For the gold brocade, Bermejo may have scored through gold leaf with a small semicircular tool to imitate the texture of the looped weave in the fabric.

In the 15th century, as now, poppies were associated with death. Bermejo has positioned them emphatically next to the devil.

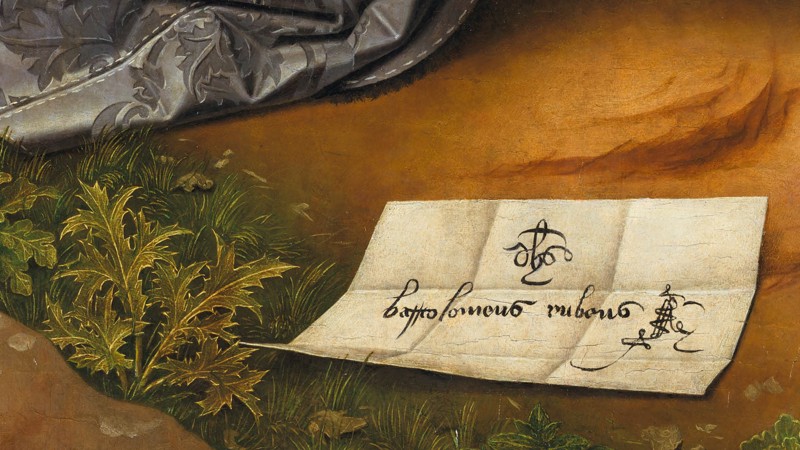

Bermejo has placed his signature prominently in the painting on a ‘cartellino’ – the fictive parchment – at the feet of the donor and Archangel. It reads ‘Bartolomeus Rubeus’, 'rubeus' being the Latin equivalent of 'Bermejo', meaning reddish.

Saint Michael was an Archangel, the highest order of angels. Bermejo conveys his heavenly qualities: his graceful, feathered wings and billowing cloak fill the canvas and give the slender saint a volume and presence that he would not otherwise have. His face is idealised – he has a serene expression, without a trace of effort or fear.

In contrast, the donor, Antoni Joan (who commissioned and financed the painting) has a naturalistic face. Here is a real man with wrinkles, stubble and a distinctive kink in his nose. It is clear that he and Saint Michael are from different worlds. Joan's sword and heavy chains indicate that he is a knight, and he holds open a book of Psalms.

The devil is made up of a combination of animals. Devils were often shown with more than one face, inspired by the description in the Bible of a seven-headed dragon. His torso is formed of a second face, and live snakes slither out of the gaping mouth in his stomach. There are reptilian heads at his elbows and at the joints of his bird-like back legs. His crocodile-like tail, which ends in a single claw, is wrapped around Saint Michael’s calf.

Saint Michael is dressed in an exquisite suit of tournament armour, made of gold and set with huge jewels, including lines of large pearls at the wrists and ankles.

The saint's breastplate reflects the towers of the holy city of Jerusalem as described in the Book of Revelation. The reflection also helps to give the impression of the armour's lustre.

He holds a small shield or buckler in his left hand. Bucklers always had a dome-shaped centre to help them deflect blows. Saint Michael's is particularly unusual – and fantastical – since it appears to be made of rock crystal. As with his armour, it is set with pearls.

Saint Michael’s resplendent cloak of cloth gold and red lining takes up much of the canvas and is painted in incredible detail. For the gold brocade, Bermejo may have scored through gold leaf with a small semicircular tool to imitate the texture of the looped weave in the fabric.

In the 15th century, as now, poppies were associated with death. Bermejo has positioned them emphatically next to the devil.

Bermejo has placed his signature prominently in the painting on a ‘cartellino’ – the fictive parchment – at the feet of the donor and Archangel. It reads ‘Bartolomeus Rubeus’, 'rubeus' being the Latin equivalent of 'Bermejo', meaning reddish.

Zoom into Saint Michael Triumphs over the Devil and read about it in depth.