Paintings underground

Who protected the National Gallery Collection during the First World War?

When the First World War began in 1914, the threat of bombs loomed over London and museums across the city needed protection. At the National Gallery, staff were coming up with a plan to store the paintings until the war was over. But it was hard to find a place to keep many works of art safe. That was until the Director, Sir Charles Holmes, had an idea that took the collection underground.

New staff training

Throughout the war, our staff worked hard to protect the collection. By October 1914, the National Gallery introduced fire and air-raid precautions and staff placed sandbags in every room to shield windows. Some even learnt to use fire hoses and others stayed overnight to guard the paintings.

As the war threat grew, the Director initially picked 50 important paintings to move to the cellar for safekeeping. Shortly after, more works of art were moved into storage across seven cellars at the Gallery.

The search for safety

Three years into the war, in 1917, shrapnel from a bomb explosion fell onto the Gallery roof. It was clear a new plan was needed to protect the paintings. At the time, Sir Charles Holmes was the Gallery Director. He took on the challenge of finding the paintings a new home.

Larger works of art had already been sent to other safe locations around the country. But where could the rest of the National Gallery Collection go? Beneath London's streets is its famous underground train network called the Tube. Holmes later wrote that he ‘recalled glimpses of mysterious sidings seen when travelling [by Tube]’. Could these be used to store paintings?

Going underground

Like the underground network, Holmes had connections. Henry Oppenheimer, whom Holmes described as one of the ‘great men of the underground’, introduced the Gallery Director to Mr Burton, the Managing Director of the Electric Railway Company.

Luckily, there was an unused underground station close to the Gallery in Aldwych. The station was 33 metres underground – about the height of seven double-decker buses. In Holmes’s own words, it was the ‘perfect subterranean fortress’.

Mr Burton generously offered the station as a place to store paintings during the war. Wasting no time, a plan was set in motion within two hours of getting the offer. Now the challenge was getting them down there.

Watching over the collection

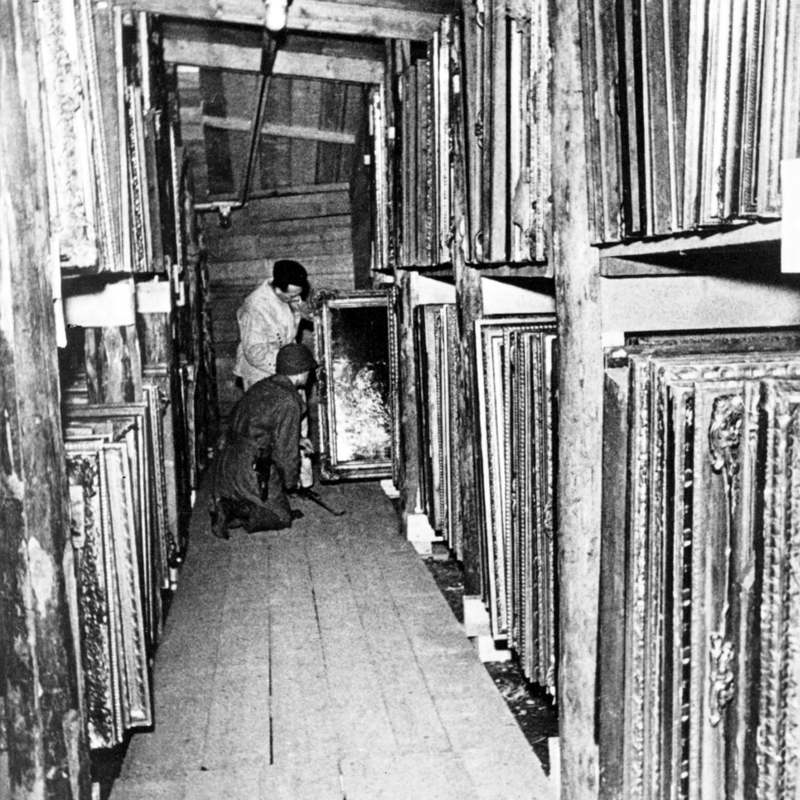

News spread fast and soon parts of other museum collections were moved into Aldwych station. This included the National Portrait Gallery, the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. With so many national treasures in one place, the government insisted on higher security.

In 1917, a letter requested that armed watchmen look after the paintings day and night. In response, a guardroom was created in the station. It was equipped so that the watchmen would not need to leave their post and the paintings remained under constant supervision.

The tight security paid off as, after the war, every painting was safely returned to the Gallery. Storing the works of art underground worked well and during the Second World War, the paintings found themselves underground once again. This time in a different location, at Manod quarry in Wales.