Safeguarding national treasures

How the National Gallery Collection was secretly evacuated during the Second World War

On 3 September 1939, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declared Britain was at war with Germany. On the same day, a team of people – including the National Gallery’s Scientific Adviser Ian Rawlins – completed a ten-day-long transportation of around 2,000 paintings to multiple locations across rural England and Wales. But this emergency evacuation was only the beginning of getting the entire collection to a safe location.

'Not one picture shall leave this island'

Many people helped to find a temporary home for the collection. Before the ten-day-long evacuation, the Gallery’s Assistant Keeper Martin Davies, who later became Director, had visited multiple sites to identify where the paintings could be safely stored. The Director at the time, Kenneth Clark, also considered sending all the paintings to Canada.

However, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was determined to keep them on British soil. 'Hide them in caves and cellars, but not one picture shall leave this island,' Churchill declared. So, where did they go?

The search for safety

Ian Rawlins was the Scientific Advisor for the National Gallery. His job was to examine paintings technically to understand more about how they were made and how best to care for them. But this was wartime, and everyone at the Gallery was all-hands on deck.

Rawlins's new role was to find a suitable location to store the collection. After looking at tunnels, caves and mines, Rawlins and his team discovered Manod quarry. It was a large slate mine that was no longer in use, located in remote north-west Wales. While it would need to be adapted, it was agreed as a safe, underground place to store the paintings.

Art on the move

Rawlins’s first challenge was transporting the paintings to the quarry. Luckily, as a railway enthusiast, he was able to advise on the transportation route. His second challenge was to do this in secret. Moving 2,000 paintings with no one noticing is difficult. But with a truck and an Elephant Case (named after its size) to store the largest paintings, the operation began.

This caused some gossip in the local community near the quarry, which was owned by Captain John Sydney Matthews. His daughter Pauline Matthews remembered her father had told the lady in the local paper shop in Llan Ffestiniog that butter was being stored in the quarry.

Hidden in plain sight

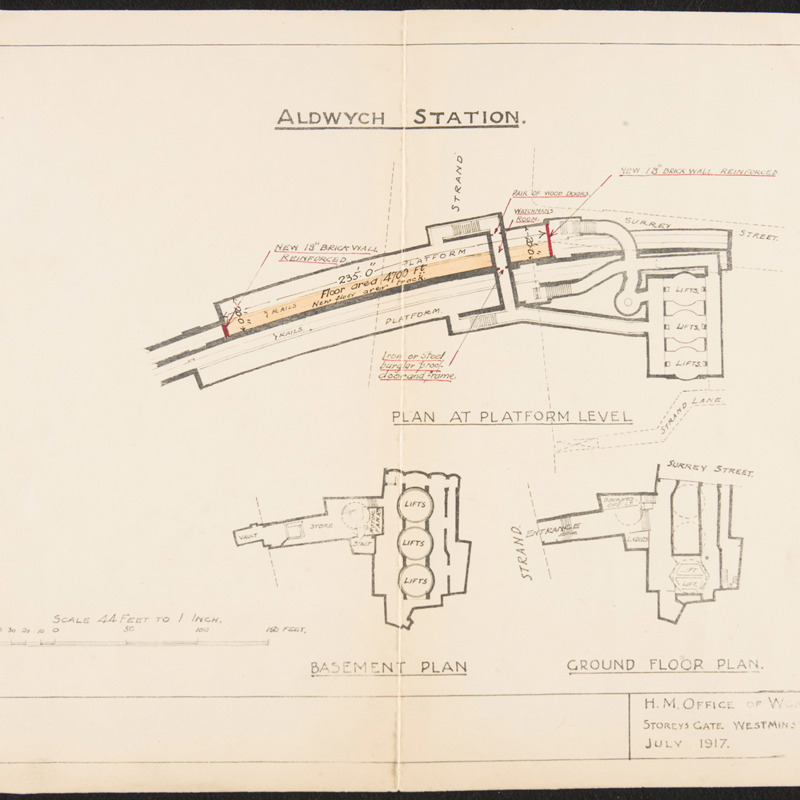

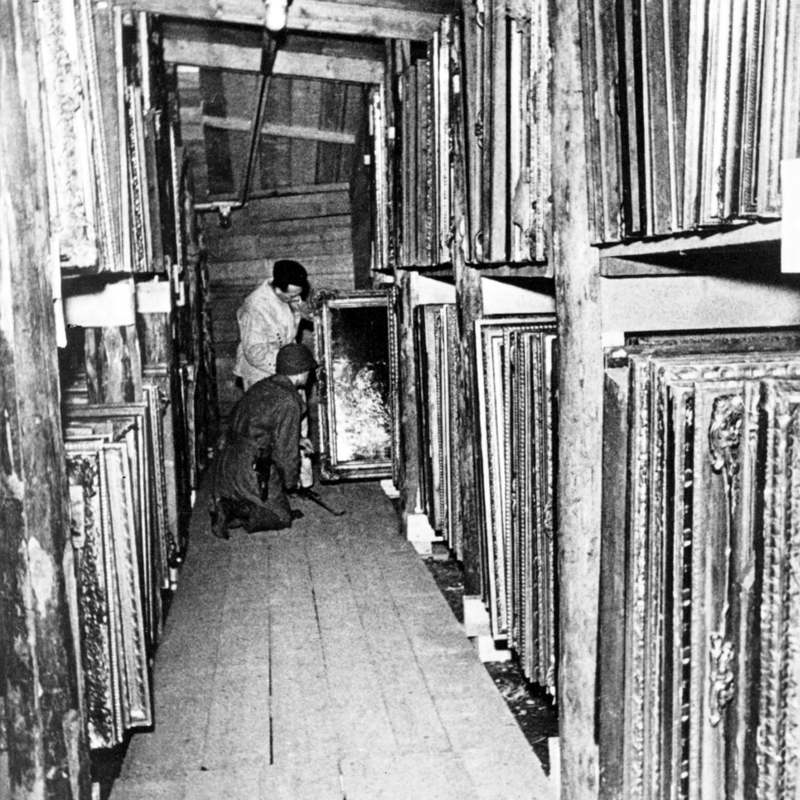

Unsurprisingly, a quarry is not naturally designed to store works of art. Explosives were used to enlarge the cave entrance to get the biggest paintings inside. Inside the quarry, a series of rooms were built to control the temperature and humidity. Special, narrow railway tracks were also laid to move the paintings from one cave to another.

The people who worked at the quarry not only helped to keep the paintings safe, they also cared for the collection. A conservation studio was built on-site and many paintings were cleaned and restored while in the quarry. Important cataloguing was also undertaken at this time by Martin Davies, which received worldwide recognition when it were published after the war ended in 1945.

After the end of the war, the paintings were all returned safely to London. This was thanks to Rawlins's impressive operation and all the staff that worked at Manod quarry.

The work undertaken while the paintings were hidden in the quarry increased our understanding of the collection and has continued to impact how it is cared for today.