A new chapter - Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands

Germination of an idea

Gauguin’s motivations for travelling to Tahiti to pursue his artistic career were many. First, his broad experience of global travel as a child, when he spent time in Lima, Peru, and then as a teenager working as a merchant marine, had introduced him to a broad range of cultures.

Once he started his career as a painter, he sought to move beyond what for him were the tame and familiar subjects of the Impressionism he had studied with Pissarro and others. His four-month journey to Panama and Martinique in 1887 with the painter Charles Laval had introduced him to the allure of tropical climates and cultures, and he invented a kind of idealised tropical, rural idyll from the island scenery and local Caribbean peoples he encountered there.

A year later, working in Arles with Vincent Van Gogh, he began to dream of starting a ‘Studio of the Tropics’, where artists could get away from the city, live cheaply, and find new and original subjects for their art that would attract new attention within the art world of avant-garde Paris.

And finally, both travel literature and the exhibitions at the Paris World’s Fair of 1889 encouraged him to think specifically of working in the French colonies, and Tahiti, in particular, beckoned as a welcoming and intriguing site where he could invent a new chapter in his art.

First Impressions – Tahiti, mystery and imagination

He arrived in Papeete, the capital town of Tahiti , in 1891. Tahiti had become a French colony in 1880, and the French presence and evidence of Western-style modernisation was, in Gauguin’s view, disappointingly pervasive. He sought to locate or to imagine scenes of the indigenous culture that he believed he had arrived too late to experience.

In his early days on the island, the Tahitian King Pomare V died, and the French takeover of the island appeared to be complete. This moment inspired him to paint, 'Arii matamoe (The Royal End)'. Gauguin’s aim was not to literally portray the king, or to document the event, but rather he created a kind of fantastic and macabre pastiche that referenced both the loss of the local leader and the sense of mystery that the island setting had sparked in his imagination.

What appears to be a severed head rests on a white presentation cloth spread over a food platter; its eyes and mouth remaining hauntingly open and suggesting some kind of enduring quasi-live presence. Figures in the background show their grief through gestures, all within a highly colourful and patterned interior inspired by sources ranging from Marquesan sculpture to Persian carpets to convey a setting that is both splendid and strange. In this scene, Gauguin wants to impress, mystify, and unsettle the French viewer through such an unexpected presentation of an imagined, exotic scene.

Early Tahitian portraits

Not all of Gauguin's early portraits in Tahiti owed so much to his imagination nor were they so constructed. At first, he had hoped to earn some money by taking portrait commissions. He completed very few; one was for an Anglo-Tahitian resident, Suzanne Bambridge. A woman of some local importance, she had married into Polynesian royalty through her husband (a chief from nearby Raiatea), and she helped host events at the Tahitian court of Pomare V. Gauguin’s portrait of her is verging on the conventional in its pose, but innovative in its highly decorative patterning, particularly in its play of colourful pattern over her expansive black court dress. But Gauguin’s depiction of her face as sober and of her figure as substantial did not please the patroness; she hid the picture away after its completion. Painting portraits for local clients would be neither lucrative nor satisfying for Gauguin.

Teha’amana – symbols and intrigue

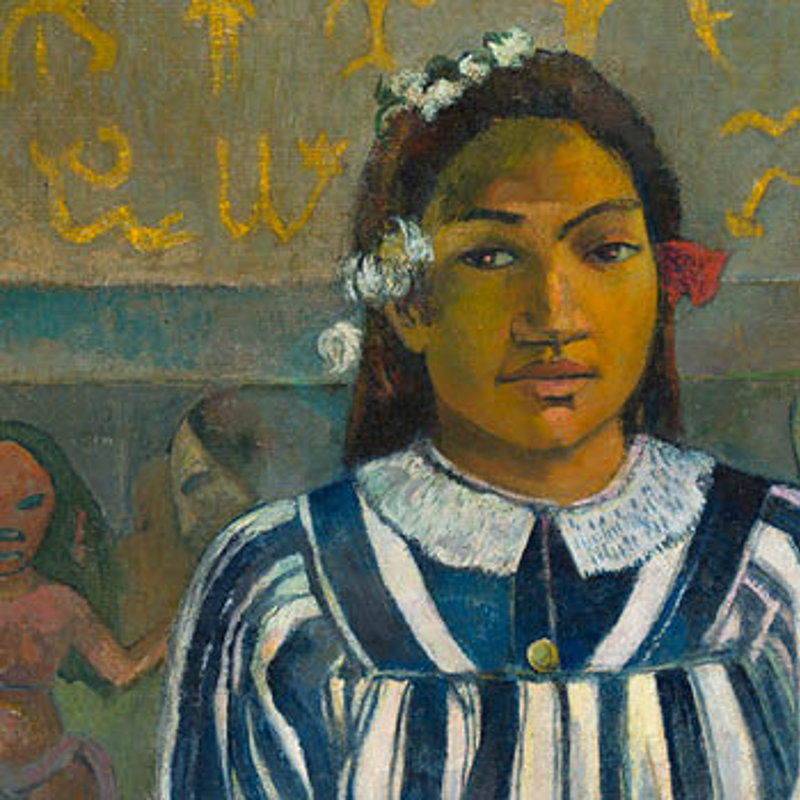

Instead, he went on to paint scenes and figures based on personal experience and his rather limited circle of acquaintances among the local Tahitians. Only one painted portrait survives in which he names the sitter as Teha’amana, his young Tahitian lover. He met her when he left Papeete to explore the island, and settled for over a year in a small village, Mataiea, on the southern coast of the island. There, he established a home in which Teha’mana agreed to live as his domestic partner.

In this picture, ‘The Ancestors of Tehamana or Tehamana Has Many Parents (Merahi metua no Tehamana)’ she poses in a fashion that was both modern and local – a dress in the modest style approved by the long-standing missionary culture, accented by a local fan and the signature Polynesian tiare flowers strewn in her hair. She sits quietly, eyes averted, assuming a kind of gatekeeper role in front of the complex display of signs and symbols inscribed in a vibrant gold on the wall behind her.

While Gauguin took these forms from cultures as diverse as carved memory boards (rongo-rongo) from Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and from the forms of Oceanic and Japanese masks, he is not offering a literal repertoire of imagery he would have encountered in Tahitian daily life. Rather, in 'The Ancestors of Tehamana or Tehamana Has Many Parents (Merahi metua no Tehamana', he is referencing (in a non-documentary way) Teha’amana’s cultural ancestry.

Given that her family was from the Cook Islands and that she herself was born in Huahine, another of the Society Islands, Gauguin probably understood her to represent an inter-island Polynesian culture that was both ancient, and broader than the single island of Tahiti itself. His display of the hieroglyphic-like writings from the rongo-rongo boards (that he would have copied from a photograph he acquired in Papeete) was intended to both intrigue and to baffle his Parisian viewer, as was the Tahitian title he painted on the canvas surface. For him, the allure and the poetry of his subject – both the sitter and her imagined setting – lay in such contradictions, and resulted from his position as a visiting French artist who had both encountered, and yet did not fully understand, either his Tahitian subjects or their culture.

Marquesan refuge

In 1901, when he moved to Hiva Oa in the Marquesas Islands, he found the culture to be less modernised than that of Tahiti. Many locals individuals caught his attention, including a sorcerer he encountered in his town of Atuona. Although he did not often paint individual men in Polynesia, he was intrigued by the figure in ‘Marquesan Man in a Red Cape’, which may well be a portrait of a ‘mahu’, or a man who lives in Polynesian society in the manner of a woman. The subject reflects Gauguin’s ongoing appreciation for the fluid gender roles he encountered in French Polynesia.

In his final years in the Marquesas, Gauguin grew increasingly critical of the colonial society. In particular, he believed that Catholic missionary work had disrupted the indigenous culture. He argued in his writings for the separation of the French state from the official French religion.

In this sculpture, which he intended to keep on permanent display at the base of the staircase to his home (nicknamed the House of Pleasure), he made a satirical image of a local cleric he particularly disliked. The sculpture ‘Père Paillard’ (Father Lechery) was a caricatural portrait carved of the local bishop, the stern and officious Joseph Martin, who since 1878 had been working to enforce Church-sanctioned conduct across the islands. In this work, and its attendant carving of a local woman Thérèse, Gauguin wants to highlight the hypocritical behaviour of the self-righteous priest, who was widely rumoured to have conducted a long-standing affair with Thérèse.

His head has the horns of a devil; a snake crawls up the figure’s back, suggesting a fallen Eden; and the compact vertical form recalls a Maori carved storage house post of the sort Gauguin has seen in New Zealand. Gauguin here combined Christian and Polynesian forms to make a sculpture that critiqued, in his view, the worst aspects of control and privilege exercised by an all too powerful Church that had worked relentlessly to disband the indigenous culture that Gauguin so treasured.

In the last two years of his life, Gauguin’s appreciation of his Marquesan neighbours brought him to a new position of advocating for a Polynesia that might ultimately be free of the most corrupting influences of colonialism, while still remaining open to the presence of curious and appreciative visitors, such as he regarded himself to be.

Dr Elizabeth C. Childs is the Etta and Mark Steinberg Professor of Art History, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Washington University, St Louis (USA)

Dr Childs is author of 'Gauguin's Portraiture in Tahiti: Likeness, myth, and cultural identity', 'Gauguin Portraits' exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Canada and the National Gallery, London 2019/2020.