Introduction to José María Velasco

The National Gallery is home to one of the world’s greatest collections of art in the Western European tradition. In the last 15 years, those parameters have broadened, as we’ve held exhibitions of North American and Australian works.

However, ‘José María Velasco: A View of Mexico’ marks the first time we’ve had an exhibition dedicated to a Latin American artist. But just who was José María Velasco?

Born in 1840, José María Velasco was the pre-eminent landscape painter in 19th-century Mexico. He trained under Italian artist Eugenio Landesio in the European tradition, at the Academia de San Carlos in Mexico City. This was the first art academy in the Americas.

Velasco was more than just a painter - he was a polymath. One of his interests was botany and this is recognisable throughout his oeuvre.

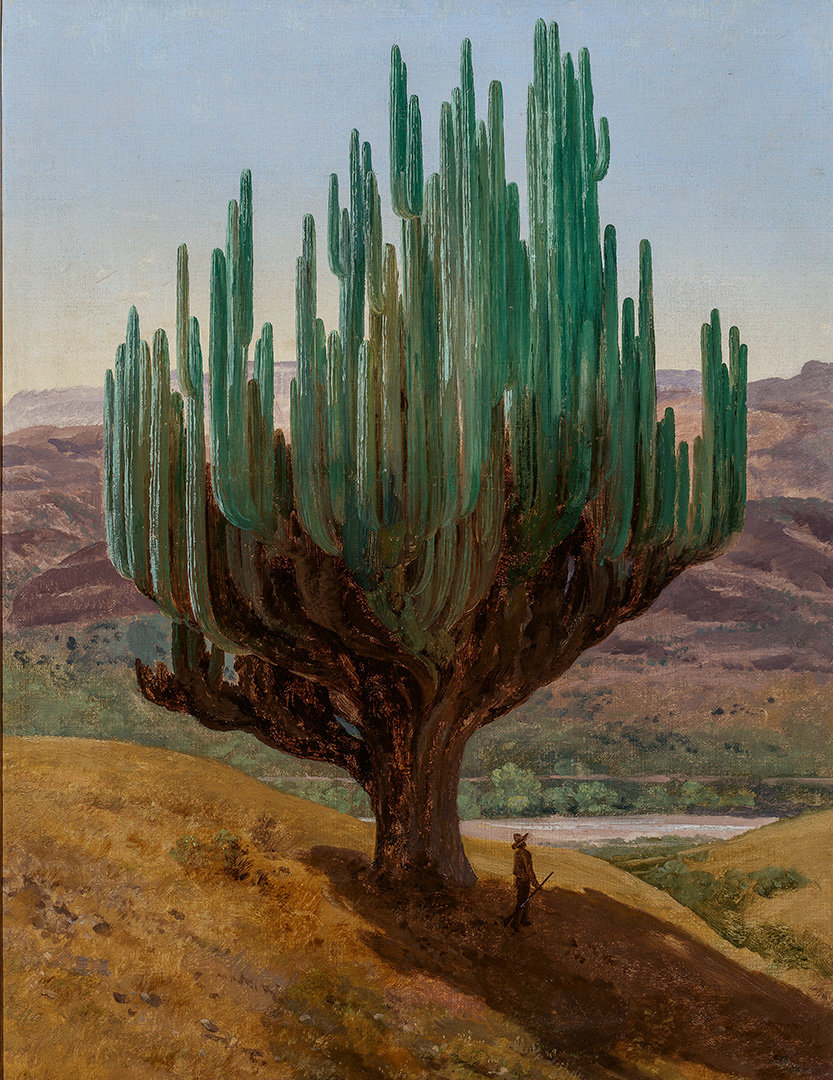

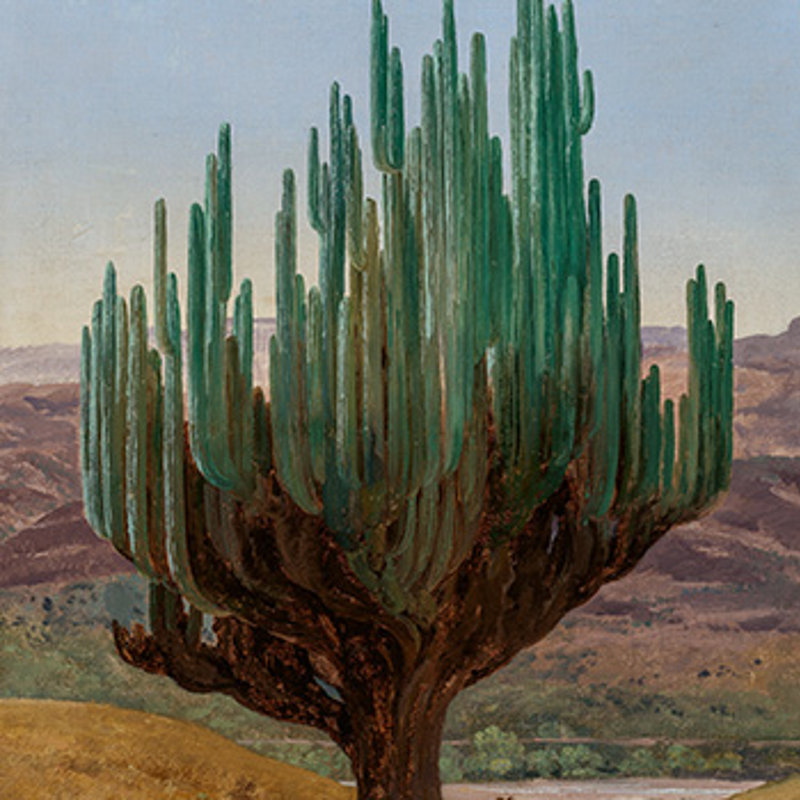

The exhibition contains analytical studies of local shrubs and cacti that informed his larger works. However, sometimes Mexican flora took centre stage: they are the focus of works like ‘The Forest of Pacho’ and ‘A Rustic Bridge in San Ángel’. Most striking of all is ‘Cardon, State of Oaxaca’, starring a breathtaking giant cactus.

Mexico City sits in a high-altitude basin, another facet of Velasco’s surroundings to which he turned his scientific eye. One work that clearly shows his interest in geology is ‘Rocas’. The painting is almost a full-length ‘portrait’ of a large rock, bursting with character.

He returns to geology in both his drawings and paintings and volcanoes regularly loom in the background of his landscapes.

Travel around Mexico and you'll be sure to encounter Velasco. His works are reproduced on postcards and lighters, much in the same way works by Van Gogh and Monet are in Europe. Outside of Mexico Velasco is less known, and this exhibition gives you the rare chance to appreciate an artist familiar to an entire nation.

Rare is perhaps an understatement – there hasn't been an in-depth Velasco exhibition outside of Mexico since 1976.

While his works are firmly rooted in Velasco’s time, he frequently alludes to Mexico’s past. Take his most celebrated work, ‘The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel’. On first glance, it is simply a landscape of the Valley of Mexico, but look harder and its secrets are revealed.

In the foreground there’s a nopal cactus and an eagle. These are not coincidental inclusions – they are fundamental to the founding story of Mexico City, according to Mexica – or Aztec – history. Both feature prominently on Mexico’s flag today.

Throughout the exhibition you’ll find allusions and symbols that tell the story of over a thousand years of human occupation of Mexico. From the pyramids of Teotihuacán that predate the Mexica empire by many centuries, to basilicas that tell the story of European colonisation and Christian conversion.

It’s not just Mexico’s complex past that interests Velasco. Just as in Europe, in the 19th century Mexico was undergoing a period of rapid industrial change.

This is exemplified in ‘The Goatherd of San Ángel’ where plumes of smoke billow in the background from the chimney of a factory, while livestock and an agave plant gather in the foreground. Through works like these Velasco shows us the changing face of Mexico.

Despite this being the first exhibition of a Mexican artist in the Gallery, one of our most famed works depicts a key moment of in the history of 19th-century Mexico.

Edouard Manet’s ‘The Execution of Maximilian’ shows the downfall of Maximilian I, a puppet ruler installed by the French. Manet was not present at the execution, instead he read about it in the newspaper and painted the scene.

It’s a reminder that the worlds of Velasco and his contemporary counterparts in Europe are not that far apart. Later in life, Velasco received a medal for his work from the emperor’s older brother Franz Josef and even painted a landscape showing the place where the emperor was killed.

Velasco painted up until his death in 1912. Towards the end of his career, he focused on smaller works, painted on postcards. These are made with a freer touch than many of his previous works, perhaps influenced by paintings he’d seen on his European travels in 1889.

From this period, we see a work showing a variety of clouds. Velasco was scrupulous when painting clouds, making notes on specific cloud forms such as cumulus and cirrus. The bottom half of this work is bare, left incomplete. He is believed to have made it on the morning of his death, dying before he could finish.