Introduction to Winslow Homer

An American great

For the first time in the UK, we present an overview of Winslow Homer (1836–1910), the great American Realist painter. Well known to many but not everyone, follow Homer's journey from magazine illustrator to sought-after artist in oil and watercolour.

His standing in the history of American art is huge. Painting at a time of enormous upheaval in America, his pictures of soldiers from the Civil War, post-emancipation Black subjects and dramatic seascapes are iconic.

Homer’s experience of catching scenes of human drama for magazines including 'Harper's Weekly' stood him in good stead. With the Civil War as the backdrop and a pass to the front line, he brought his intuition for ‘behind-the-scenes’ reality to mud-splattered, exhausted soldiers, precarious tree-perched sharp shooters, and often humdrum, unsentimental images of hardship - a theme he carried over into later works.

He attended formal training in art only briefly before setting his own agenda. Established as an artist, he painted not only in oil but was also a talented watercolourist producing striking images of hurricane-lashed palms in the Caribbean and sparkling seascapes such as ‘Diamond Shoal’ (1905), his last known watercolour.

Charles, two years older than Homer, gave his brother a copy of Eugène Chevreul's 'De la loi du contraste simultané des couleurs' (1839), an influential 19th-century treatise on colour. Homer, in fact not a natural colourist, later referred to it as his ‘Bible’. They shared a love of fishing.

He made two trips across the Atlantic. The first in 1866 to Paris where he saw the art of Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet. Homer, like other artists of the age, was influenced by Japanese prints that were arriving via eastern trade routes.

Aged 45 he unexpectedly visited Tyneside where he lived for a year and a half (1881–2). He witnessed the tough lives of the fishing community and the Life Brigade in the small town of Cullercoats on the North Sea coast. Gales, rough seas, frantic rescues as well as day-to-day local scenes characterise his English pictures.

Homer’s paintings are mostly of life outside. Unavoidably so in the case of reporting from the Civil War’s front line but he also sought out nature. He was attracted to nature’s power and the obstacles it created for humans to overcome. The sea had an especially strong draw for Homer whether he painted a dramatic lifeboat rescue or a person at the sea’s mercy adrift in the Gulf Stream. There is huge tension, but not melodrama, in the sea’s unpredictability and the potential for disaster.

Homer is recognised for his images of formerly enslaved people at a time of great social change. He catches sensitive moments of everyday life in two post-war paintings: ‘The Cotton Pickers’ of 1876 and ‘Dressing for the Carnival’ of 1877.

Unlike some artists of the 19th century, we don’t have a lot of information about Homer’s personal life. From records of conversations and comments that have passed down the years, he emerges as, what could be described as, an ‘interesting character’. He comes across as someone who most likely didn’t suffer fools gladly, wasn’t a stranger to the odd terse response and, in later years, led a relatively reclusive life on the Maine coast, north of Boston. His Prouts Neck studio, a building that his brother Charles helped him set up, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965. It was bought by the Portland Museum in 2006 who restored it to how Homer would have known it and it was reopened in 2012.

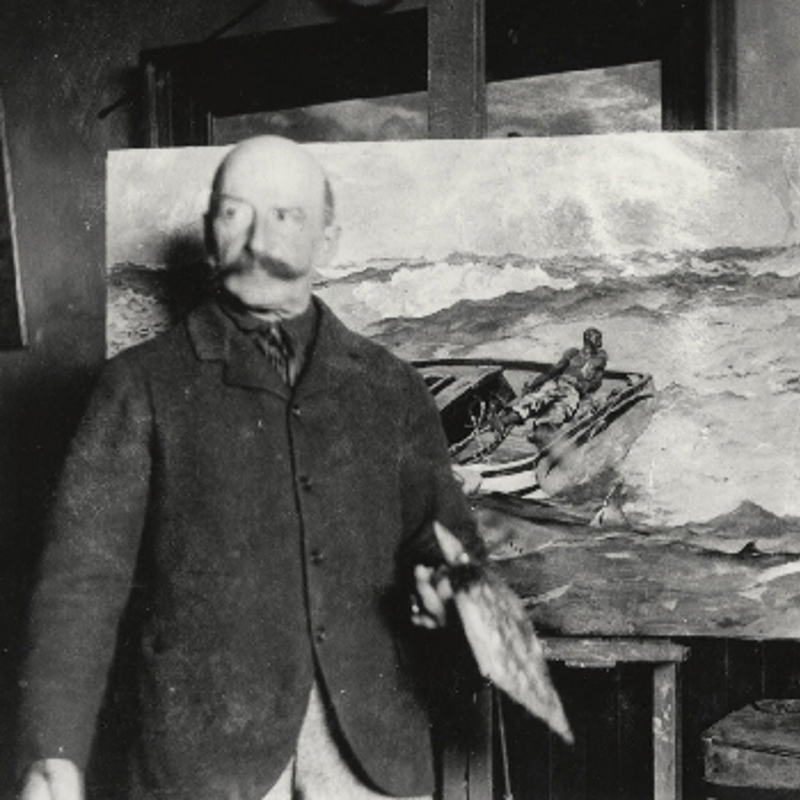

Title image: Winslow Homer with 'The Gulf Stream' in his studio, about 1900, gelatin silver print, by an unidentified photographer. Image courtesy of Bowdoin College Museum of Art