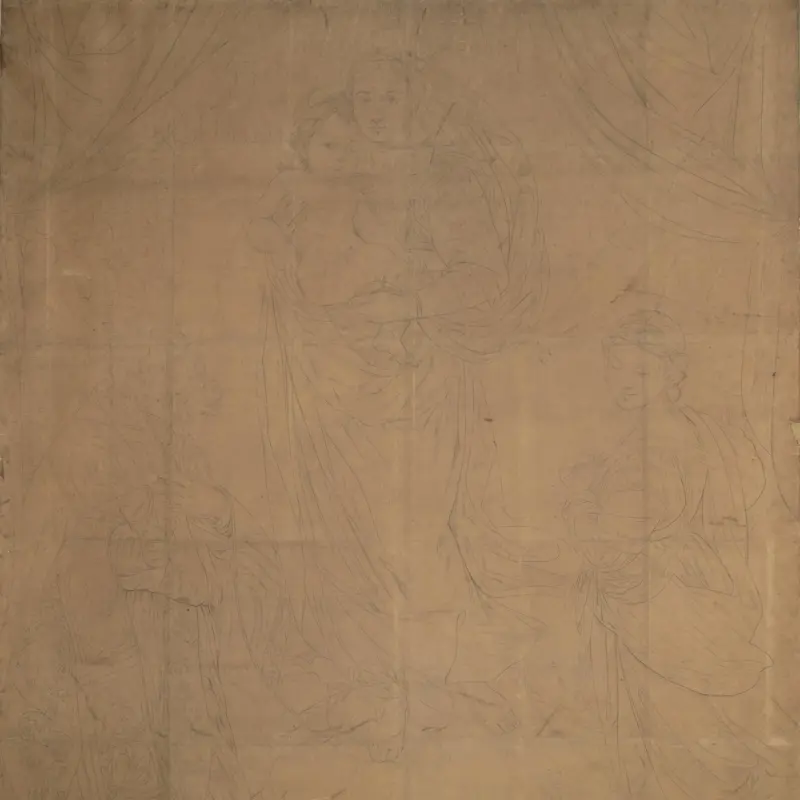

After Raphael, 'The Madonna and Child', probably before 1600

About the work

Overview

This is a copy of Raphael’s Virgin and Child known as ‘The Bridgewater Madonna’. The original is on loan to the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh from the Duke of Sutherland’s collection.

The copy is similar in size and in most colours and follows Raphael’s style closely, making it difficult to attribute to a known artist. Its origin is uncertain but it possibly dates from the late sixteenth century. The copy is very precise, except for the gauzy drapery which covers Christ’s nudity. This is clearly a later addition, probably dating from the nineteenth century.

Raphael adapted Christ’s dynamic twisting pose from Michelangelo’s relief sculpture, the Taddei Tondo (Royal Academy of Arts, London), and Leonardo’s Madonna of the Yardwinder (one of two known versions is on loan to the National Galleries of Scotland). Although he had previously depicted Christ lying across his mother’s lap, Raphael had never before given the pose so much movement nor invested the scene with so much drama.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- The Madonna and Child

- Artist

- After Raphael

- Artist dates

- 1483 - 1520

- Date made

- probably before 1600

- Medium and support

- oil on wood

- Dimensions

- 87 × 61.3 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Wynn Ellis Bequest, 1876

- Inventory number

- NG929

- Location

- Not on display

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Previous owners

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Cecil Gould, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools’, London 1987; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Bibliography

-

1828J. Christie, Catalogue of the Very Valuable Collection of Capital Italian, French, Dutch and English Pictures: The Property of the Earl of Carysfort, Deceased, London, 14 June 1828

-

1854G.F. Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain: Being and Account of the Chief Collections of Paintings, Drawings, Sculptures, Illuminated Mss. […], vol. 2, trans. E. Eastlake, London 1854

-

1877R.N. Wornum, Descriptive and Historical Catalogue of Pictures in the National Gallery, British School, Foreign Schools, London 1877

-

1877London, National Gallery Archive, NG17/4: Annual Report of the Director of the National Gallery to the Treasury for the Year 1876, 1877

-

1924T. Borenius and J.V. Hodgson, A Catalogue of the Pictures at Elton Hall in Huntingdonshire, in the Possession of Colonel Douglas James Proby, London 1924

-

1962Gould, Cecil, National Gallery Catalogues: The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools (excluding the Venetian), London 1962

-

1971L. Düssler, Raphael: A Critical Catalogue of His Pictures, Wall-Paintings and Tapestries, trans. S. Cruft, London 1971

-

1987Gould, Cecil, National Gallery Catalogues: The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools, London 1987

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.