Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas, 'Young Spartans Exercising', about 1860

About the work

Overview

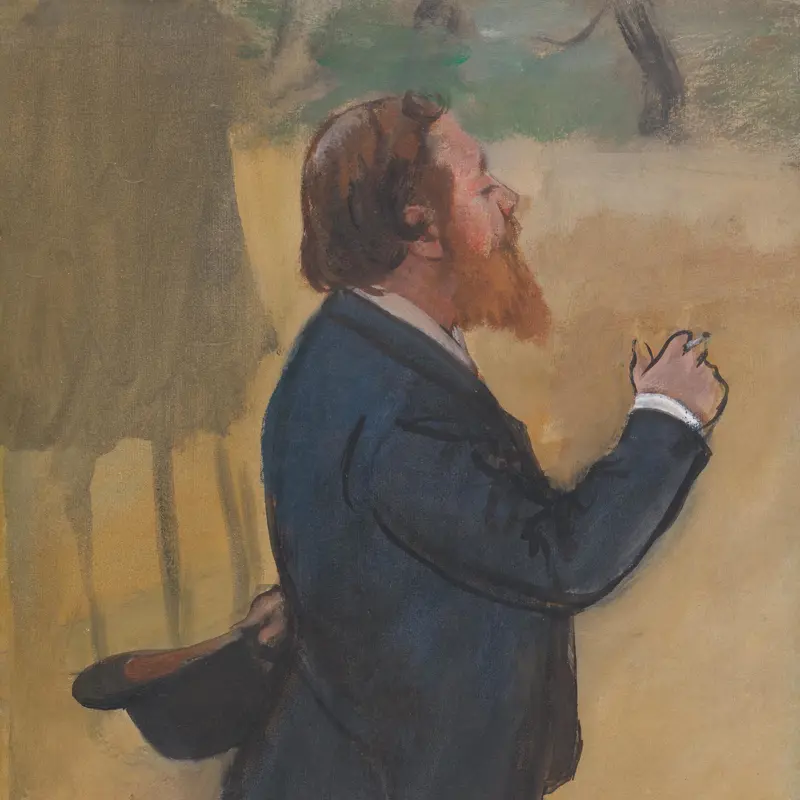

The painting illustrates a passage from the Life of Lycurgus by the Roman historian Plutarch, which describes how Spartan girls were ordered to engage in exercise – including running, wrestling and throwing the discus and javelin – and to challenge boys. However, this may be a scene of courtship rather than competition, as aspects of the girls' hairstyles and poses correspond with accounts of such rituals in Plutarch’s writing. In the middle distance a group of women, mothers of the children, surround the elderly Lycurgus, who drew up the rules of Sparta. Beyond them is the city of Sparta, overlooked on the left by Mount Taygetus, from which unwanted Spartan infants were thrown.

Degas abandoned his first attempt at the painting (now in the Art Institute, Chicago) and made substantial changes to this second version as he tried to modernise it, replacing the classical features of the adolescents with more contemporary faces. The picture had great significance for him, and he kept it in his studio all his life.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- Young Spartans Exercising

- Artist

- Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas

- Artist dates

- 1834 - 1917

- Date made

- About 1860

- Medium and support

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 109.5 × 155 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, Courtauld Fund, 1924

- Inventory number

- NG3860

- Location

- Room 41

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Frame

- 18th-century Italian Frame

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Martin Davies, with additions and some revisions by Cecil Gould, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: French School: Early 19th Century, Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, etc.’, London 1970; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

2011HeroìnesMuseo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza8 March 2011 - 5 June 2011

-

2011Degas and the NudeMuseum of Fine Arts, Boston9 October 2011 - 5 February 2012Musée d'Orsay12 March 2012 - 1 July 2012

-

2015Delacroix and the Rise of Modern ArtMinneapolis Institute of Art18 October 2015 - 10 January 2016The National Gallery (London)17 February 2016 - 22 May 2016

-

2016Painters' Paintings: From Freud to Van DyckThe National Gallery (London)23 June 2016 - 4 September 2016

-

2018Courtauld Impressionists: From Manet to CézanneThe National Gallery (London)17 September 2018 - 20 January 2019

-

2019Degas at the OpéraMusée d'Orsay23 September 2019 - 19 January 2020National Gallery of Art (Washington DC)1 March 2020 - 12 October 2020

Bibliography

-

1890G. Moore, 'Degas: The Painter of Modern Life', Magazine of Art, XIII, 1890

-

1933G. Jeanniot, 'Souvenirs sur Degas. II', Revue universelle, LV, 1933, pp. 152-74

-

1946P.-A. Lemoisne, Degas et son oeuvre, Paris 1946

-

1952D. Martelli, 'Gli Impressionisti', in A. Boschetto (ed.), Scritti d'arte di Diego Martelli, Florence 1952, pp. 98-110

-

1954D. Cooper, The Courtauld Collection: A Catalogue and Introduction, London 1954

-

1957Martin Davies, National Gallery Catalogues: French School, 2nd edn (revised), London 1957

-

1958J.S. Boggs, 'Degas Notebooks at the Bibliothèque Nationale II: Group B (1858-1861)', The Burlington Magazine, C/663, 1958, pp. 196-205

-

1964P. Pool, 'The History Pictures of Edgar Degas and Their Background', Apollo, LXXX/32, 1964, pp. 306-11

-

1966W.M. Ittmann, 'A Drawing by Edgar Degas for the Petite Filles Spartiates Provoquant des Garçons', Register of the Museum of Art, The University of Kansas, III/7, 1966, pp. 38-49

-

1967J.S. Boggs, Drawings by Degas (exh. cat. City Art Museum of St Louis, 20 January - 26 February 1967; Philadelphia Museum of Art, 10 March - 30 April 1967; Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, 18 May - 25 June 1967), Saint Louis 1967

-

1969D. Burnell, 'Degas and His Young Spartans Exercising', Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, IV, 1969, pp. 49-65

-

1970Davies, Martin, and Cecil Gould, National Gallery Catalogues: French School: Early 19th Century, Impressionists, Post-Impressionists etc., London 1970

-

1974J. Lassaigne and F. Minervino, Tout l'oeuvre peint de Degas, Paris 1974

-

1976T. Reff, The Notebooks of Edgar Degas. A Catalogue of the 38 Notebooks in the Bibliothèque Nationale and other Collections, Oxford 1976

-

1977A.B. Price, Puvis de Chavannes: A Study of the Easel Paintings and a Catalogue of the Painted Works, Phd Thesis, Yale University 1977

-

1977N. Broude, 'Degas's Misogyny', Art Bulletin, LIX/1, 1977, pp. 95-107

-

1979I. Dunlop, Degas, London 1979

-

1982K. Roberts, Degas, Oxford 1982

-

1984R. Brettell, Degas in the Art Institute of Chicago (exh. cat. Art Institute of Chicago, 19 July - 23 September 1984), Chicago 1984

-

1985C. Salus, 'Degas' Young Spartans Exercising', Art Bulletin, LXVII/3, 1985, pp. 501-6

-

1986D. Sutton, Edgar Degas: Life and Work, New York 1986

-

1986L. Nochlin, 'Letters: Degas's Young Spartans Exercising', Art Bulletin, LXVIII/3, 1986, pp. 486-8

-

1986C.S. Moffett, 'Disarray and Disappointment', in Fragonard Les The New Painting: Impressionism 1874-1886, Oxford 1986, pp. 293-309

-

1987R. Thomson, The Private Degas, London 1987

-

1988R. Gordon and A. Forge, Degas, New York 1988

-

1988R. Thomson, Degas: The Nudes, London 1988

-

1988N. Broude, 'Edgar Degas and French Feminism, circa 1880: "The Young Spartans", the Brothel Monotypes and the Bathers Revisited', Art Bulletin, LXX/4, 1988, pp. 640-59

-

1988E. Camesasca, 'A proposito di Edgar Degas', Critica d'arte, LIII/17, 1988, pp. 57-64

-

1988M.K. Meller, 'Exercises in and Around Degas's Classrooms, Part I', The Burlington Magazine, CXXX/1020, 1988, pp. 198-215

-

1988J.S. Boggs et al., Degas (exh. cat. Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, 9 February - 16 May 1988; National Gallery of Canada, 6 June - 28 August 1988; Metropolitan Museum of Art, 27 September 1988 - 8 January 1989), New York 1988

-

1989D. Druick, 'La petite danseuse et les criminels: Degas moraliste?', in Musée d'Orsay, Degas Inédit: Actes du Colloque Degas, Musée d'Orsay, 18-21 avril 1988, Paris 1989, pp. 225-50

-

1989C. de Couëssin, 'Technique, transformations dans les toiles de Degas des collections du musée d'Orsay', in Musée d'Orsay, Degas Inédit: Actes du Colloque Degas, Musée d'Orsay, 18-21 avril 1988, Paris 1989, pp. 145-59

-

1990F. Milner, Degas, London 1990

-

1992N. Broude, 'Edgar Degas and French Femininism circa 1880', in N. Broude and M.D. Garrard (eds), The Expanding Discourse: Femininism and Art History, New York 1992, pp. 269-80

-

1994G. Tinterow and H. Loyrette, Origins of Impressionism, (exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994), New York 1994

-

1995A. Callen, The Spectacular Body, Science, Method and Meaning in the Work of Degas, New Haven 1995

-

1996R. Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874-1886: Documentation, San Francisco 1996

-

1996J.S. Boggs, Degas, Chicago 1996

-

1996W. Davies, 'Gender', in R.S. Nelson and R. Shiff (eds), Critical Terms for Art History, Chicago 1996, pp. 220-33

-

1996R. Brettell, 'Thomas Eakins and the Male Nude in French Vanguard Painting 1850-1890', in D. Bolger and S. Cash (eds), Thomas Eakins and the Swimming Picture, Fort Worth 1996, pp. 80-97

-

1997Glasgow Museums, The Birth of Impressionism: From Constable to Monet (exh. cat. McLellan Galleries, 23 May - 7 September 1997), Glasgow 1997

-

2000B. Thomson, Impressionism: Origins, Practice, Reception, London 2000

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2001T. Llorens et al., Forma: El ideal clásico en el arte moderno (exh. cat. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, 9 October 2001 - 13 January 2002), Madrid 2001

-

2003M. Lucy, 'Reading the Animal in Degas's Young Spartans', Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, II/2, 2003, pp. 1-18

-

2004D. Bomford et al., Degas (exh. cat. The National Gallery, 10 November 2004 - 30 January 2005), London 2004

-

2006P. Kaina, 'Illegible Bodies: Edgar Degas's "Young Spartans Exercising', Object, IX, 2006, pp. 26-45

-

2007A. Green, French Paintings of Childhood and Adolescence, 1848-1886, Aldershot 2007

-

2007W. Hofmann, Degas: A Dialogue of Difference, London 2007

-

2007R. Thomson, 'Degas et Henner: Comparaisons et contrastes', La Revue du Musée d'Orsay, 24, 2007, pp. 6-19

-

2007C. Sisi et al., Nel segno di Ingres: Luigi Mussini e l'Accademia in Europa nell'Ottocento (exh. cat. Complesso museale Santa Maria della Scala, 6 October 2007 - 6 January 2008), Milan 2007

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.