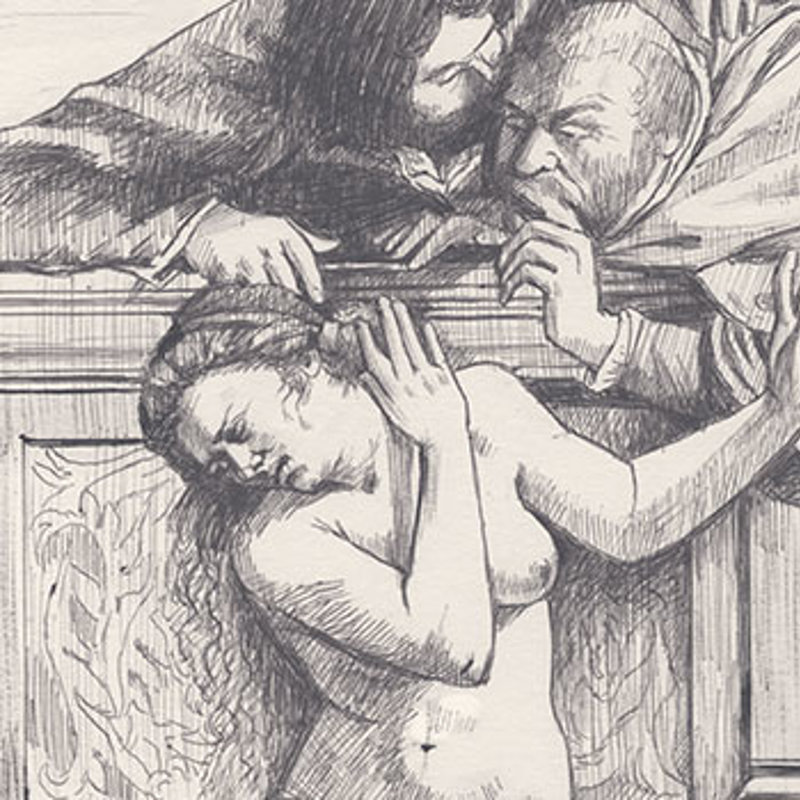

Testimony at the trial

The first time we hear Artemisia’s voice is at the trial that saw the painter Agostino Tassi (about 1580–1644) convicted of her rape. There, the testimony of the eighteen-year-old Artemisia has come down to us in the form of a transcript of the trial's proceedings (conserved at the Archivio di Stato, Rome). In addition to describing the sexual assault, Artemisia repeatedly asserts that she is telling the truth and to test the veracity of her statement she is tortured using the 'sibille' (cords wrapped around the fingers and pulled tight). As the cords tighten, she is recorded as saying:

"I have told the truth and I always will, because it is true and I am here to confirm it wherever necessary."

Then, turning to Tassi, who had falsely promised her marriage, Artemisia quips:

“This is the ring that you give me and these are your promises”.

From these words that have come down to us, we can already appreciate Artemisia’s spirit, resilience and strength of character; traits that also emerge from the letters she wrote later in life.

Letters to her lover

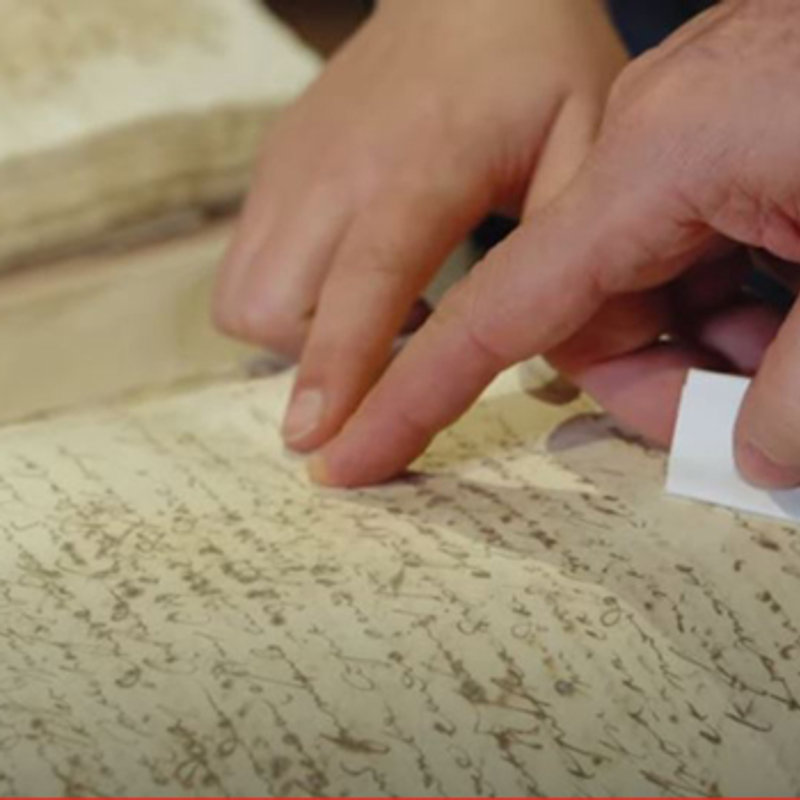

In 2011, a group of letters written by Artemisia and her husband Pierantonio Stiattesi (b. 1584) to her Florentine lover Francesco Maria Maringhi (1593–after 1653) was discovered. Mostly exchanged once the couple were living in different cities – Artemisia in Rome, Maringhi in Florence – they offer a glimpse into Artemisia’s most intimate thoughts and feelings.

Artemisia taught herself to read and write in Florence: at the trial in 1612 she claimed to be illiterate (or, at least, she could hardly read and could not write). The grammatical mistakes and phonetic spellings in Artemisia’s writing merely add to the strong character that emerges from her letters.

Artemisia’s passion is not just directed at Maringhi: she communicates with equal fervour about the urgent return of her belongings, the recent death of her four-and-a-half-year-old son Cristofano, and both her jealousy and yearning for her distant lover. Her personality comes sharply into focus, forcing us to adjust any preconceptions we might have of her as a victim. Instead, a witty, passionate woman emerges, determined to control her own destiny and gain the respect she deserves.

Artemisia and Maringhi’s love affair probably began around 1618: the first letter in which Artemisia addresses him tenderly (‘mio carisimo core’) probably dates from around this time. In these private letters to Maringhi Artemisia describes her state of mind and her appearance. In one, she describes having put on considerable weight, claiming that he would barely recognise her and likening her physical transformation to Ovid’s 'Metamorphoses' (thus also playfully alluding to their amorous liaisons). Her reference to Ovid is just one of numerous citations in her letters, revealing Artemisia to be far more cultured than had previously been thought. References to the Renaissance poets Petrarch and Ludovico Ariosto suggest that she was familiar with such writings – though probably through recitations or the spoken word, rather than having read these texts at first hand.

Artemisia’s fiery personality and vulnerability also come through her letters: in one, written just five days after the death of her little boy, Artemisia tells Maringhi that fortune has turned its back on her. Distraught with grief, she claims that her misfortunes are far greater than his and she goes on to reproach her lover for the brevity of his letters (which she reads as a sure sign of his diminishing affection).

Letters to her patron

After this relatively intense but brief period of exchange of private letters in 1618–20, there is silence. We are only brought back in touch with Artemisia’s voice in the 1630s and ‘40s, once in Naples, where she settled until the end of her life (except for a brief trip to London). The letters that survive from this period are very different: the majority are dictated to scribes or secretaries and many no longer exist in the originals (and are known only through transcriptions).

Addressed to contacts and patrons – the antiquarian Cassiano dal Pozzo, the astronomer Galileo Galilei, the Sicilian collector Antonio Ruffo – Artemisia’s letters are principally concerned with professional matters. She speaks of payments, commissions and paintings being sent all over Europe as she attempts to seek permanent employment elsewhere. She complains bitterly about life in Naples, the high cost of living and her enduring financial difficulties, and yet Artemisia’s career prospered. She ran a thriving workshop in Naples in which her sole surviving child, her daughter Prudenzia, presumably trained.

It was in her letters from Naples that Artemisia made some of her boldest statements, asserting her position as a serious professional. In 1649, while defending the price she is charging for an ambitious work containing eight figures, two dogs, a landscape and water, she assures the collector Ruffo that:

"with me Your Illustrious Lordship will not lose and you will find the spirit of Caesar in the soul of a woman."

Artemisia was determined to be considered equal to any male artist and, whilst acknowledging preconceptions of the time that "a woman’s name raises doubts until her work is seen", she assures him that her works "will speak for themselves." Just a few months later she famously proclaimed to the same patron: "I will show Your Illustrious Lordship what a woman can do."

We have to make do with fragments – testimonies at the rape trial, private communication with her lover, letters to patrons and clients – to hear Artemisia’s voice. And yet, 400 years later, her words ring loud and true, conjuring up an image of a fiercely independent woman who, despite the gender constraints of the time, was determined to find success and take control of her personal and professional affairs.

Written by Letizia Treves, The James and Sarah Sassoon Curator of Later Italian, Spanish, and French 17th-century Paintings at the National Gallery, and curator of Artemisia.