Meticulously rendered in ballpoint pen, 'I Know What I Am' weaves Artemisia’s artworks with her life story, the politics of art patronage and religious turmoil of her times.

Here Gina Siciliano talks to Letizia Treves about her inspiration, intentions and the artistic choices she made in creating this beautifully illustrated book.

For those unable to see 'Artemisia' in person, you can also watch an online tour of the exhibition with Letizia Treves.

Letizia Treves (LT): In 2007 you saw 'Judith beheading Holofernes' in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence. Was this the first time you had come across Artemisia’s work? And was it this painting that inspired you to make Artemisia the subject of your book?

Gina Siciliano (GS): I discovered Artemisia’s work in an art history class at Pacific NW College of Art in Portland, Oregon. I was blown away by her and immediately wanted to make a graphic novel about her. Then, after I graduated in 2007, I saw the Uffizi 'Judith Beheading Holofernes', which solidified the idea in my mind.

LT: 'I Know What I Am' is your first graphic novel. It’s been seven years in the making and you must have done extensive research – not easy, given that Artemisia studies have gained pace in recent times. What were your main sources and how did you ensure that your text was up-to-date (regarding biographical and archival findings, for example, or new paintings coming to light)?

GS: I started with a year of research — reading anything I could find about 17th-century Italy, women, sexuality and painting. I had to become familiar and comfortable enough with Artemisia’s world before I could create a believable narrative. I did a lot of inter-library loans and, since I’m a second-hand bookseller, I’m constantly around books. I looked at scholars’ bibliographies, tracking the research that others did. I continued researching while working on the book too, trying to absorb as much as possible. I took another year to do research before starting the third segment of the book, as it deals with Naples, Venice, Florence, and London. I had to get a feel for all those different environments. At that point I bought a University of Washington library card, which opened up a whole new world!

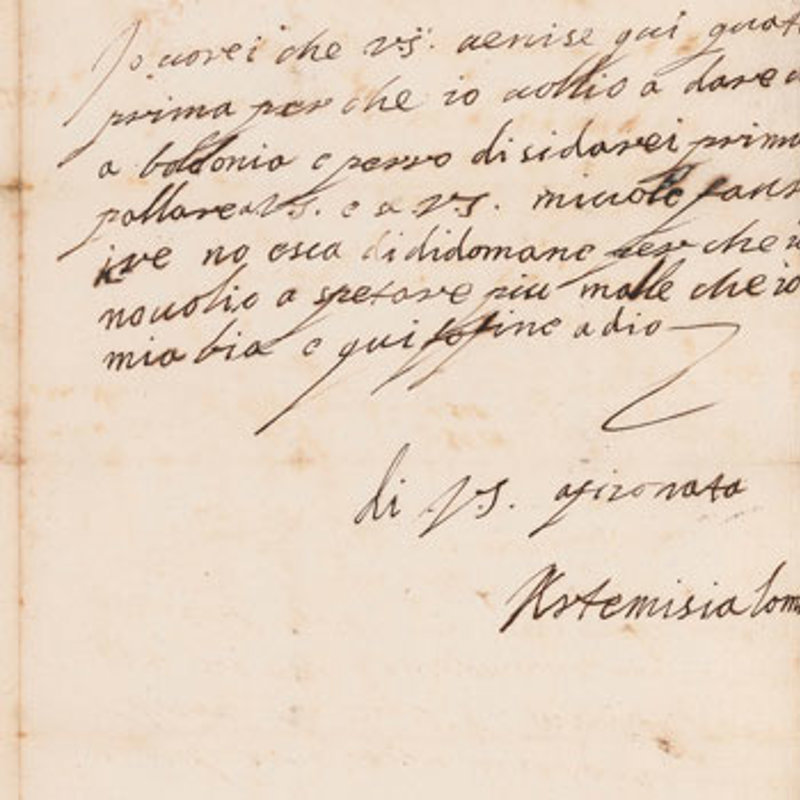

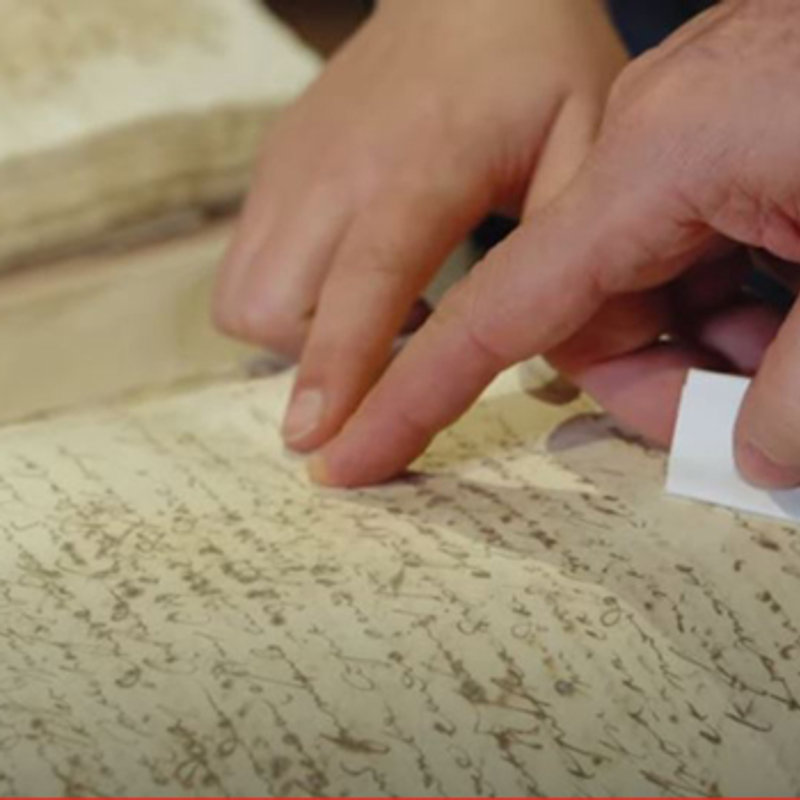

I became familiar with a core group of Artemisia scholars, and started thinking of history as something that fluctuates, a sort of moving dialogue. It’s impossible to be completely up-to-date because new information is always surfacing, and scholars are debating about every bit of it all the time. But I still tried. After the discovery of the letters from 1620 in the Frescobaldi archives, I went back and changed that portion of the book.

When the book 'Artemisia in a Changing Light' came out in 2017, I addressed some of those new revelations in the notes section at the back of the book. The notes especially demonstrate my involvement with this ongoing debate about Artemisia and her work. We’ll never know the ‘real’ Artemisia, all we can do is continue the discussion, and showcase all the sources that lead us to draw conclusions.

LT: As I discovered, working on the subject intensely over the past couple of years – first on the National Gallery’s acquisition of the 'Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria' and then on the exhibition – there’s a lot of literature on Artemisia Gentileschi, but this is the first graphic novel. Why do you think that is? There’s obviously been a growing trend and interest in graphic novels on artists, such as Milo Minara’s on Caravaggio (2015) or Vanna Vinci’s on Frida Kahlo (2017).

GS: I’ve been making comics forever, since I was a kid, so combining words and pictures feels like a completely natural expression. Artemisia’s story lends itself well to the format.

LT: The book is divided into three parts (or acts): her early life (Part 1); the rape and ensuing trial (Part 2); and the rest of her life (Part 3). What shaped your decision to dedicate two-thirds of the book to the first 18 years of her life (Parts 1 and 2 close in 1612, whereas Part 3 covers a 50-year period)? Was it because the rape is the best-known episode in Artemisia’s life? Or simply because this episode and the ensuing trial presented greater dramatic possibilities? After all, the documents relating to her later life are patchy and don’t conjure up as vivid a picture of the world she moved in as, say, the various witness statements from the trial.

GS: For so long it felt like we didn’t know much about Artemisia’s later life. Scholars are now able to piece together a much more cohesive outline of her life and work, very different from when I began. Initially I planned to end the story after Artemisia splits with her husband, but I soon realised I had to do a full biography. I wanted to feature an older woman protagonist. I feel like the perspectives of women over forty are generally scarce, within art, film, comics, literature, media and society at large. Another reason for making a complete biography was to show that life goes on after extreme trauma, that survival is possible. The impact of sexual abuse cannot be underestimated; it often casts a shadow over the lives of survivors. Yet, Artemisia’s life didn’t end after she was sexually abused – she kept pushing onward; pushing beyond that shadow, but always living with it. The structure of the book reflects this.

LT: You’ve said that one of the key goals of your book was to put Artemisia ‘in context’. You evoke the cities in which she lived and worked so well (Rome, Florence and Naples) and I wondered how much of this was down to personal experience: did you travel to these places or did you just read extensively around the subject?

GS: Besides a whirlwind trip around Europe in 2007, I never had the money, time, or resources to travel.

LT: Then the fact that these sections of your book are so evocative is even more impressive!

LT: I want to talk a little about the creative process. Perhaps you can tell us how you actually go about putting together a book like 'I Know What I Am'? Do you start with pencil drawings of Artemisia’s paintings? How do you know which ones to draw? How do you plot your storyline: do you mock it up on screen or paper first?

GS: First I make notes, lists, and outlines. I work on the writing, then the visuals, and finally I shape it all into thumbnails (rough, preliminary mock-ups of the pages in pencil). The goal was to invent as little as possible, to string together the facts with fiction. Each page is like a complex puzzle to work through, with its own mood, theme, and composition. I was lucky enough to work with a fabulous editor, Jason Conger. He spent many hours critiquing the early thumbnails, especially the voice, flow, and pacing. We passed the thumbnails back and forth, until eventually I was ready to use them as blueprints for drawing the actual pages – pencil first always, layering on the ball-point pen last.

A biography of a painter must feature the paintings, so I wove Artemisia’s paintings into the chronological narrative. I chose the main body of work that Artemisia is known for, the paintings that are most definitely by her, those with less controversy over attribution. When the viewer sees a painting on the page alongside images of the social/political climate and/or Artemisia’s personal life, the viewer sees the painting put into context. This is part of why comics are such a great medium for an artist biography.

LT: One of the things I find most compelling – and most successful – about your book is the balance between words and images (be they drawings of Artemisia and the characters in her life, or drawings after her paintings). How did you decide what to put into words and what to convey in pictures?

GS: Choosing what to draw and what to write is one of the fundamental challenges for anyone making comics. It means communicating in two languages simultaneously. Each page has its own criteria that must be met. So many factors go into these decisions. Sometimes it’s gut instinct. For instance, the page where Artemisia discovers that Prudenzia is her one surviving child – it just felt right to strip away the text and let the reader be there with Artemisia in her darkest moments, with those black panels and minimal design. Some of these decisions have to do with time and pacing, figuring out how much space to allocate to each different episode and aspect of Artemisia’s life and work. The more I learned about 17th-century Europe, the more important it felt to convey this era politically and socially, which led to some wordy/text-heavy areas. But making a wordy graphic novel felt necessary in order to put Artemisia into context. Otherwise, we’re just projecting our own modern mindset onto her.

LT: In the flesh, Artemisia’s paintings are incredibly strong – the figures are generally life-size, the lighting dramatic and she uses a bold, rich colour palette. Somehow, you’ve managed to convey an equally forceful presence in your drawings, even though they are relatively small in scale and exclusively in monochrome. Did you ever consider producing your novel in colour?

GS: I never felt like I could afford colour. For many years I self-published my comics, which is expensive. I got used to colour never being an option (except for the cover). I didn’t know that Fantagraphics would publish 'I Know What I Am' until the end of the journey. I submitted it to numerous publishers, and nobody wanted it for so long, I assumed that I’d have to continue self-publishing it with limited funds. Also, when I first set out to do this, so much of it was outside of my comfort zone. So I wanted the medium at least to be comfortable and familiar, and I’d already developed a soft, layered, almost brushy look with ball-point pen.

LT: Your book includes all of Artemisia’s key paintings – many of the pictures in our exhibition are reproduced in your book, because I took the same selective approach in picking out loans for the show. How many of Artemisia’s paintings do you know at first hand? Were you able to travel (to Italy and across USA) to see her works, or did you use images reproduced in books and on the internet?

GS: I saw the Uffizi 'Judith beheading Holofernes' back in 2007 and last autumn I saw the earlier version of 1612. Before this painting travelled to the National Gallery for your show, it was here at the Seattle Art Museum, as part of an exhibition of important Italian paintings from the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte in Naples (I participated in that exhibition and drew comics for it). Besides those two paintings, I’ve only seen reproductions.

I copied Artemisia’s paintings from photos in books; an immensely gratifying, meditative, and instructive process. I could see why copying the works of Old Masters was considered the foundation of learning to be an artist during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. I learned a lot by doing this — different things in the paintings emerged that I hadn’t noticed before. It required staring at every inch of each painting for hours, and it made me feel closer to Artemisia.

I’ve always been a low-wage worker, so travelling to see the paintings was never an option. I might’ve had more support if I’d gone back to school for this, but I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in debt. This year I finally had the money to do a small book tour and of course come to the National Gallery, but then the pandemic happened. For my entire adult life I wanted to see these paintings in person more than anything in the world… and now I can’t. This year people are grieving over lost loved ones, lost jobs, lost homes; and I am grieving over lost paintings.

LT: I can honestly say that I share your frustration, and I know that the same disappointment is felt by so many people around the world. The reaction to the National Gallery’s 'Artemisia' exhibition has been overwhelming, especially from people who are not naturally drawn to ‘old art’ (Old Master paintings). In the little time we’ve been able to open, we’ve seen attendance to the exhibition increase among younger audiences, almost certainly because Artemisia’s personal story and powerful paintings resonate with contemporary society. Are you experiencing a similarly enthusiastic response? Is your book crossing over genres and reaching new audiences? (It’s already been reprinted how many times?)

GS: 'I Know What I Am' was released on the heels of the #MeToo movement, even though the book was brewing long before. Somehow the timing was perfect – Artemisia’s work was showcased at the Seattle Art Museum and the National Gallery in London just as my book was released, so now we are on the second print run. A few educators/teachers have told me that they are using my book as a teaching tool. I think the book serves as a bridge between academia and a broader, more general audience, a reflection perhaps of my place in-between as well. Diving deep into Artemisia’s world for so long changed me and changed how I see the world. Artemisia was my gateway into history, so I can see how she provides that for others too. We have to dig deeper to find the voices of minorities in history. It’s our responsibility to seek evidence of what poor people, black people, brown people, women, and queer, and disabled people were up to hundreds of years ago, and how they survived. When we learn about their survival, we learn about our own survival.

LT: I think your book will really stand the test of time: it has secured a place on my bookshelf, for sure. Now what? Are you working on another graphic novel?

GS: I’m always working on and thinking about a lot of different projects, but drawing comics is my safe space, the medium that I always come back to. Without giving away too much, I’ll say that I’m not done with the Italian Renaissance, and I’m slowly planning and researching another graphic novel dealing with that world. I’m also working on what I refer to as ‘essay comics’– shorter segments, followed by notes, which could be put together into a book at some point. I just finished a ten-page ‘essay comic’ about the George Floyd protests, Black Lives Matter, and some of my favourite black American writers like James Baldwin and Lorraine Hansberry.

LT: Gina, thank you so much for talking to me – I’m just so sorry that we couldn’t do this in person, in front of the paintings. And congratulations again on your beautiful book – it’s such a remarkable achievement – and I wish you all the best for your future projects.