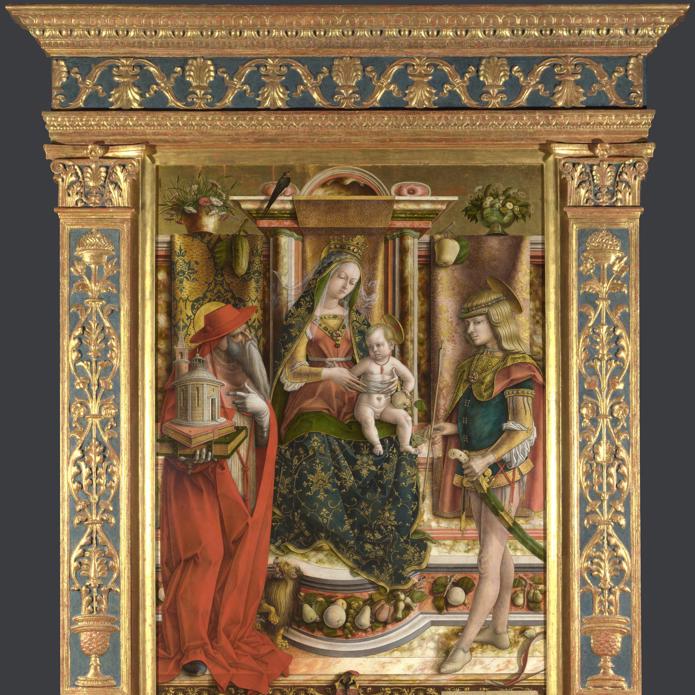

Carlo Crivelli, 'La Madonna della Rondine (The Madonna of the Swallow)', after 1490

About the work

Overview

This large panel comes from an altarpiece painted in 1491 by Carlo Crivelli. It was made for the Ottoni family chapel in the Franciscan church at Matelica, in the Italian Marches.

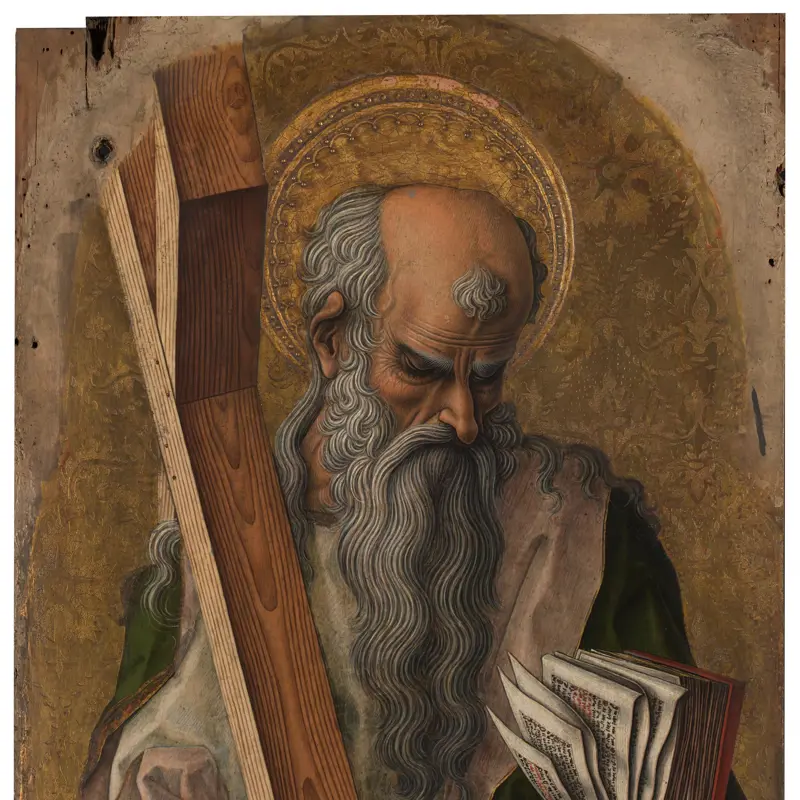

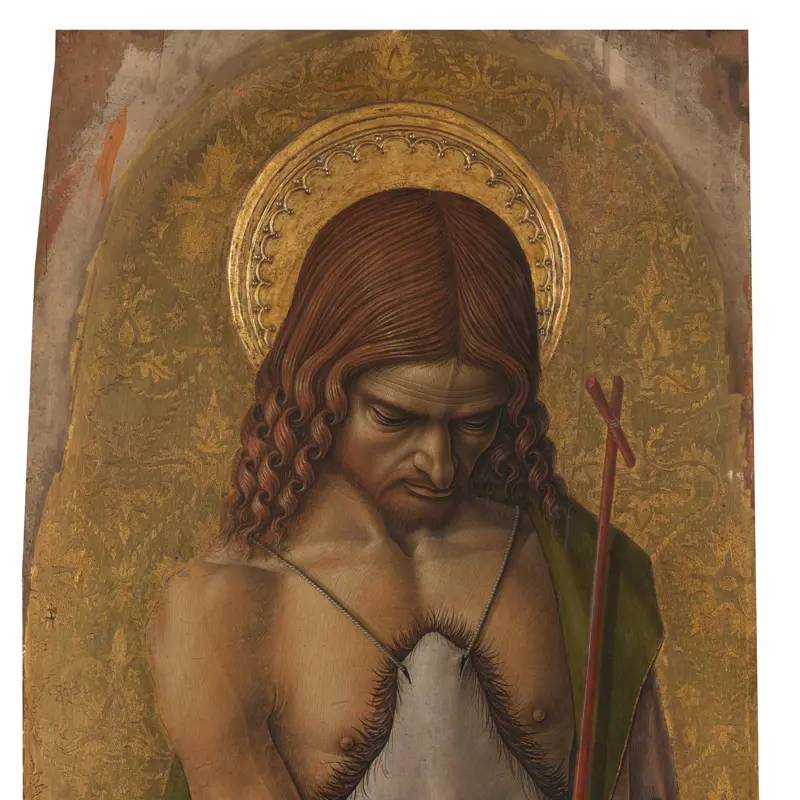

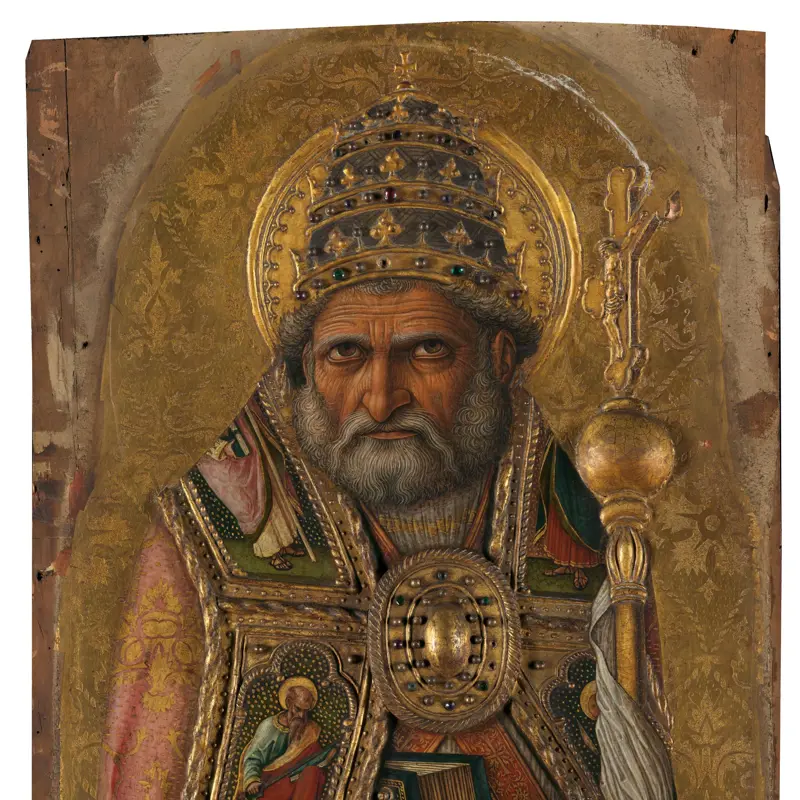

The Virgin, to whom the chapel was dedicated, appears crowned as the Queen of Heaven, with the Christ Child on her knee. The saints on either side of her reflect the concerns of the patrons, one a churchman, the other a soldier: Saint Jerome was the patron of scholars and theologians, while Sebastian was the patron of soldiers. The swallow of the title, a symbol of Christ’s Resurrection, perches above Mary’s head.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- La Madonna della Rondine (The Madonna of the Swallow)

- Artist

- Carlo Crivelli

- Artist dates

- about 1430/5 - about 1494

- Part of the group

- Altarpiece from S. Francesco dei Zoccolanti, Matelica

- Date made

- after 1490

- Medium and support

- egg tempera with some oil on wood

- Dimensions

- 150.5 × 107.3 cm

- Inscription summary

- Signed

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1862

- Inventory number

- NG724.1

- Location

- Room 10

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Frame

- 15th-century Italian Frame with Later Interventions (original frame)

Provenance

Additional information

For further information, see Alistair Smith et al., ‘An Altarpiece and its Frame: Carlo Crivelli's ‘Madonna della Rondine’’ in ‘National Gallery Technical Bulletin’, Vol.13, 1989; for further information see the Technical Bulletin.

Exhibition history

-

2011Devotion by Design: Italian Altarpieces before 1500The National Gallery (London)6 July 2011 - 2 October 2011

-

2023Paula Rego: Crivelli's GardenThe National Gallery (London)20 July 2023 - 29 October 2023

Bibliography

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the group: Altarpiece from S. Francesco dei Zoccolanti, Matelica

Overview

This large altarpiece was painted by Carlo Crivelli in 1491 for a family chapel in the Franciscan church in Matelica, a small town in the Italian Marches. The Ottoni were the local ruling family – you can see their coat of arms placed conspicuously on the bottom edge of the main panel.

The location heavily influenced the altarpiece’s design. The Ottoni chapel was tall and needed a tall altarpiece: including the frame and predella (the bottom tier) the painting is approximately 2.5 metres high. There was a large window on the back wall of the chapel – which was unusual – so the altar and altarpiece had to be on the side walls. This painting was on the left wall; the light in it comes from the upper right, mimicking the actual light in the chapel.