Author: Amanda Lillie

4. Interpreting the geometric pavement

One reason why architecture appears so frequently in Italian Renaissance painting is that the depiction of buildings was particularly desirable at a time when artists were learning and demonstrating their ability to work with a perspectival system. To display the full range of perspectival skills, a picture needed to include measured pictorial space bounded by geometric and rectilinear forms which proclaimed their scale and proportions.21 Perspective therefore made paintings more architectural. A paved floor, road or piazza, were all ideal grounds on which to lay out a grid of intersecting lines, to establish the base for the correct diminution of forms receding into the pictorial distance.22

Although much has been written about the ways in which chequerboard floors and pavements create a convincing illusion of deep pictorial space, they can affect the picture, its meanings and the viewing process in many other ways. For instance, the creation of measurable distances within the image determines physical, psychological and spiritual relations between the figures and places depicted. Alberti may have intended this when he noted that these pavements affected the whole composition and ultimately the visual narrative, which he considered to be the painter’s most important goal.23 We might expect a rigid grid to fix and limit the viewing process, but small changes to strongly structured designs or repeated patterns are quickly registered by viewers and can trigger a range of reactions. Furthermore, the positioning of figures on the geometric stage could be delicately and precisely choreographed to create particular meanings and responses.

The result may defy the apparent clarity of spatial exposition, as Piero della Francesca’s famously indecipherable ‘Flagellation’ shows us (fig. 7). It is partly these tensions and surprises in pictures which at first seem to be rule driven and predictable, that continue to draw us to Italian Renaissance paintings.

In ‘Saint Jerome in his Study’ (fig. 8) Antonello da Messina’s wonderfully intricate pavement is foreshortened in a virtuoso display of perspectival brilliance. Its complicated, lively pattern, its colours, the reflections of light across its tiled surfaces, its swift recession over the almost empty expanse of floor towards the far reaches of what seems to be a great church interior, are all set against the figure of the saint who is relatively enclosed and close. The pavement measures the distance between the viewer and the saint, and between the outer entrance arch in the viewer’s world and the distant landscape. It plays an essential role in Antonello’s extraordinary exploration of the near and the far.24 The near is rendered by a heightened sense of architectural materials – seen as though through a magnifying glass – each block of the finely jointed masonry differentiated from its neighbour, and each block a study in the varied mineralogical composition of sandstone (fig. 9).

This magnification of the foreground is set up in relation to extreme diminution through glimpses of the far distance beyond the church windows, where landscape begins to become diffused as it recedes towards a tiny strip of light where the hills meet the sky (fig. 10). This minute scrutiny of a whole spatial continuum could itself be a metaphor for the act of studying. In order to show us Saint Jerome as the ideal scholar Antonello seems to have discovered a way of painting that most difficult of subjects – the life of the mind.

The role of perspective in lending the subject additional meaning is also to be found in the topmost drawing on the sheet of five compositional studies sometimes attributed to Antonello da Messina (fig. 11). The isolation of the pietà-like Madonna and Child in an empty room is rendered more explicit and acute by the extent of empty floor around them, spelled out in each sepia and white square (fig. 12).

Likewise, the cross-bars of the window behind them and the isolated tree in the form of a cross to the right act as predictors of the Crucifixion – fast forwarding to another time – and are therefore purposefully set at a distance behind the Madonna and Child. If it were not for the receding perspective laid out in the squared floor, these crosses of window and tree would look much closer, and the perceived spatial differentiation between the Madonna and Child symbolically superimposed on the cross of the window bars would not function properly. Even on such a small scale in this set of investigative drawings, the artist shows a profound interest in the creation of settings and remarkable control over the relationship between figures and architecture, and between the viewer and the image, and over the spiritual role played by an architectural setting.

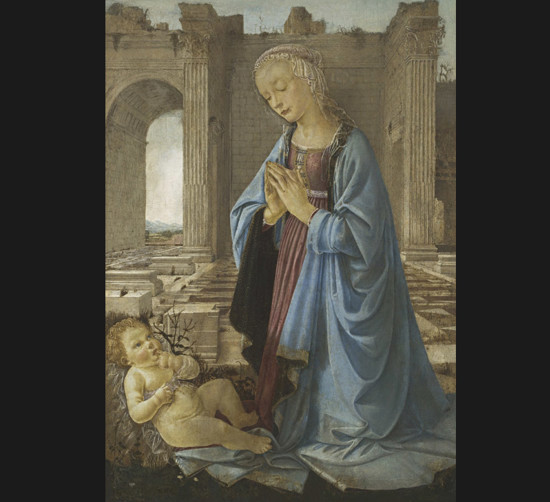

Just as the artist of the five compositional studies used the squared floor to establish difference and distance between the figures and the symbolic forms behind them, so Verrocchio in his ‘Ruskin Madonna’ (fig. 13) used paving to establish distance between the Madonna and Child placed in their own distinct pictorial field – a strip of meadow in the immediate foreground – and the architecture behind them. Because of this the pavement assumes resonances, as the weeds growing through its cracks and its display of wear over time help to create the nostalgia and sense of loss that pervade the picture. The distance set up in the receding paving becomes a visual metaphor for the constantly receding ancient past. Even a squared pavement can stir the emotions.

The preparatory techniques used by Sebastiano del Piombo to draw the perspectival pavement in ‘The Judgement of Solomon’ (fig. 14) are close to those of Verrocchio’s ‘Ruskin Madonna’. Both artists incised parallel horizontal lines (transversals) with a stylus across the whole width of the panel, with diminishing gaps between each line. In each case these lines are visible running across the picture under the drapery and figures, showing how the perspectival pavement preceded the depiction of the figures. In both these pictures the perspectival scheme is meticulously and confidently drawn and incised (figs. 15, 16, 17 and 18).

Although the geometry of Verrocchio’s paving scheme is complex, including alternating dark red and white diamonds and squares, the orthogonal lines of the perspective converge simply and consistently at a single vanishing point just below the praying hands of the Madonna, as though her prayer gesture draws together and contains the essential message of the work (fig. 15). In the case of Sebastiano’s unfinished painting the single vanishing point is located at the top of the third step of Solomon’s throne (immediately below the ram’s nose, fig. 18). Since this almost certainly marks the spot where Sebastiano intended to place the dead baby, this is another case where the artist literally pinpoints the key to the picture’s meaning. The baby’s death brought about the judgement of Solomon.25 Vanishing points are set up with a sense of purpose to focus the viewer’s attention on a significant thing, and sometimes to point out a metaphoric or underlying meaning.

Although we think of perspectival diminution and geometric pavements as technical achievements that create a crisp, linear, unyielding aesthetic effect, the ruined condition of the paving in Verrocchio’s ‘Ruskin Madonna’ and the unfinished state of Sebastiano’s ‘Judgement’, produce delicate and subtle results, especially where the pavements recede into far distance. In Sebastiano’s painting the floor is allowed to recede into the aisle space to the far right until its compressed diamonds become mere slivers of white paint brushed softly in their allocated slots (fig. 19).

Likewise, in Verrocchio’s ‘Ruskin Madonna’, the dissolution of the hard surface into a shimmer of lines where the pavement meets the landscape at the end of the archway helps to make the transition between architecture and nature, but also depicts objects literally disappearing from sight (fig. 20). It is because the process begins at the base of the painting as something measured and geometrically inscribed, that its disappearance – as a measured action by the painter comprehended by the viewer – seems almost miraculous or magical. To see it happen within the space of a few inches on a canvas or panel in front of us is a particular type of artistic demonstration, marking the transition from near to far, from visibility to invisibility, from possession to loss. It is in these passages where forms dissolve towards distant horizons that a sense of nostalgia builds.

Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Study for the setting of "The Adoration of the Magi"’ (fig. 21) is a paradigmatic example of a working drawing for the perspectival system which underpinned paintings like these. The squared pavement was drawn first, then the architecture of stairways and arches was slotted into the pavement grid. The figures of men, horses, ox and camel followed after this, each placed in relation to the diminishing floor. This suggests a clearly defined order of execution, but almost all features of the architecture, as well as the figures, continued to evolve.26 Leonardo’s initial ideas for ‘The Adoration of the Magi’ were for a much more architectural painting to be dominated in the centre by a huge pitched roof for the stable, the humble structure in which Christ was born, contrasting with the elaborate ruined stairways and arches to the left. He then omitted the stable and replaced it with a grassy mound and tree, both already sketched into the drawing as an alternative idea. Landscape is allowed to take over and architecture becomes a motif (although admittedly a prominent one) symbolising the decay of antiquity or the old order to be replaced by the new. The drawing reveals the rigorous perspectival structure which underpins the work, enabling Leonardo not only to construct a convincing sense of distance and of the relative proportions of figures set in space, but also to create a narrative out of the figures moving through and across elaborate and subtly defined spatial fields.

This interplay between figure and architecturally determined perspectival space became a hallmark of Renaissance painting, almost as if it were its own aesthetic category. The close spacing of the horizontal lines in the pavement accelerates the apparent rate of recession so that we seem to be hurtling towards the relatively high horizon, and Leonardo gave up drawing the final section of horizontals as the lines would have merged into each other (fig. 22).

This is very like what occurs in the distant perspectives of Sebastiano and Verrocchio, the melting or blurring of form conveying a sense of infinite distance which is both mysterious and fascinating, drawing us towards it with an almost magnetic force. Here too, step-by-step, rectangle by rectangle on the squared pavement, Leonardo demonstrates the transition from an exact and comprehensible description of space in the foreground towards its disappearance in the distance. These geometric pavements can produce an optically mesmerising effect, just as their repeated performance by Renaissance artists may seem like the staged rituals of scientific experiments on display.

Botticelli’s ‘Adoration’ tondo (fig. 23) is an interesting case of an outdoor scene set in a landscape with irregular stony ground, hills, a river valley, woodland and sky, which might not have required a perspectival grid. There is certainly no chequerboard pavement here. Yet the architectural nature of Botticelli’s composition, its geometric plan being that of a great cross within a circle, its elevations created by rectangular blocks and curving arches stretching across the panel and intersecting with its circumference, determined the need for one. Furthermore, both figures and architecture had to be integrated into a precise scheme of perspectival recession. Close examination of the painting reveals that the architecture was indeed incised in the gesso ground before the figures, which were fitted into the architectural framework. Many of the parallel lines (transversals) of the grid are visible to the naked eye (fig. 24), as well as some of the lines leading into depth (orthogonals).

This tightly structured underpinning of the picture could have resulted in a strictly symmetrical painting, but Botticelli deliberately avoids this. For example, the vanishing point is not positioned at the very centre of the circle, which is also the focal point of the subject where the Christ Child lies. Instead it is in the void behind the stable, in the dark hole in the broken wall immediately behind the ass and the ox. Botticelli then set about dismantling some of the most regular features of the architecture, leading to a picture which is very finely balanced between clarity and complexity, between crowds and open air, between an asymmetrical ruin and a perfectly round panel. Botticelli thus avoids any of the rigidity or plodding predictability associated with the most explicit type of perspectival geometry.

The decision not to introduce squared paving is as significant as the decision to include it. The throne of Domenico Veneziano’s otherwise strongly geometric image of the ‘The Virgin and Child Enthroned’, is placed in a meadow, rather than on a floor (figs. 25 and 26).

In Carpaccio’s drawing ‘Saint Augustine in his Study’ a dominant floor pattern would have disturbed the play of light and shadow across the ground (fig. 27).

In Domenico Veneziano’s ‘A Miracle of Saint Zenobius’ the crazy paving of the street adds to the uncontrolled grief of the wailing mother. Many other paintings in this publication include measured floors which are subtly drawn so as not to dominate the composition. An artist like Beccafumi takes this still further in his ‘Story of Papirius’ (fig. 28) by leaving expanses of pale unarticulated ground – a decision which allows the figures to float across the panel and contributes to the dreamlike evocation of Ancient Rome. A strictly defined space would have destroyed this sense of a distant, unknowable past, and the buildings, each of which has its own powerful, distinctive geometry, seem to rise like spectres on an indeterminate stage.

Read further sections in this essay

To cite this essay we suggest using

Amanda Lillie, 'Constructing the Picture' published online 2014, in 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting', The National Gallery, London. http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture/constructing-the-picture/interpreting-the-geometric-pavement

21. These pictures have what Damisch called ‘the allure of a demonstration’, Damisch 1995, p. 326.

22. Alberti 1972, p. 11 ‘checker-board construction’; Alberti 1991, pp. 13–4 ‘foreshortened grid or tiled pavement’; Alberti describes drawing the pavement in perspective. For analysis of perspectival pavements see Krautheimer 1992, pp. 247–8; Field 1997, pp. 26–9; Damisch 1995, pp. 293–8.

23. Alberti 1972, pp. 57–8: ‘This method of dividing up the pavement pertains especially to that part of painting which, when we come to it, we shall call composition’.

24. See essay by Roccasecca in Florence and Paris 2013. Distance is the third property of vision listed by Alhacen after light and colour.

25. The living baby would have been held by the executioner to the right.

26. See Popham 1946, nos 39–53; London 2010, cat. no. 53, pp. 210–1.