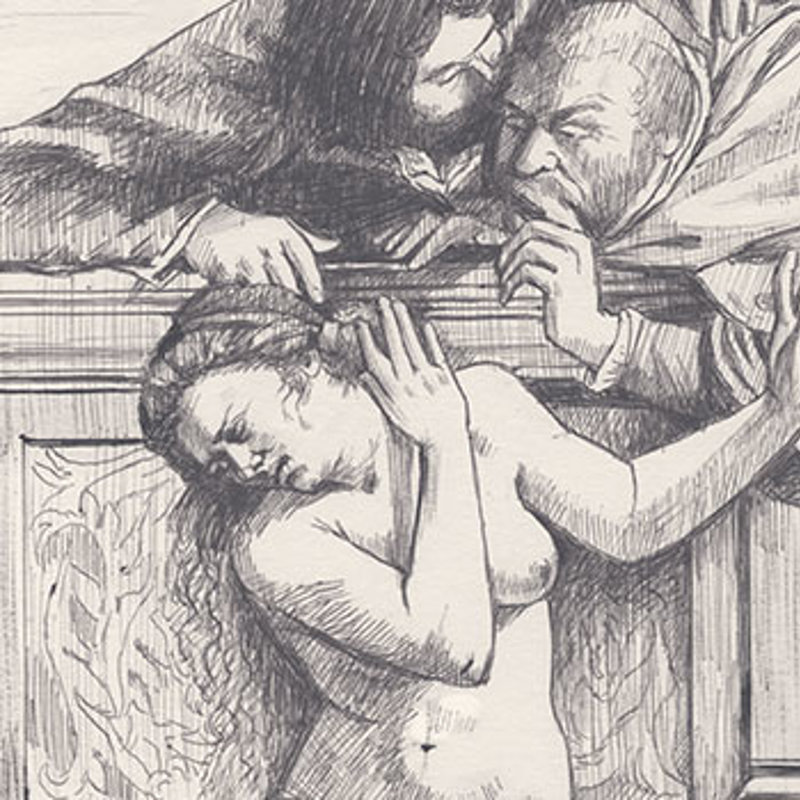

The Old Testament Apocryphal story of the virtuous Susannah being spied on as she bathes in her garden is given a new, female perspective by Artemisia. Here, she focuses on the heroine’s modesty and obvious distress at being surprised by two lecherous old men. Susannah’s unsuccessful attempt to conceal her nakedness and pull away only seems to draw the elders – and us, as viewers – even closer. Artemisia made changes to the composition while painting, introducing more space around Susannah’s head to emphasise her isolation and vulnerability.

The Old Testament Apocrypha tell how Judith, a Jewish widow, saved the city of Bethulia from the Assyrians by killing their general, Holofernes. Dressed in her finest clothes, she entered the enemy camp and, after dining with Holofernes in his tent, waited for him to fall asleep before cutting off his head. Artemisia imagines the aftermath of this violent act, with Judith and her maidservant fearful at being discovered and preparing to make their escape. Holofernes’s oversized sword rests on Judith’s shoulder, its blade’s proximity to her exposed neck a vivid reminder of what has just taken place.

Reclining in an isolated bedchamber, the first-century BC Egyptian queen Cleopatra has just committed suicide following the death of her lover Mark Antony. The poet Plutarch tells how Cleopatra was bitten by an asp hidden in a basket – the snake can be seen slithering beside her. Artemisia paints Cleopatra already succumbing to its poisonous bite: her head rests languidly on her hand, her skin is deathly pale and her lips are turning blue. In the background Cleopatra’s two maidservants burst into the room, just in time to see their queen expiring her last breath.

The story of Lucretia, her rape by Sextus Tarquinius and her subsequent suicide to protect her honour is taken from the Roman historian Livy. It is not hard to imagine, following her own experience of sexual violence, that Artemisia would have felt a particular empathy for this female hero. The tightly cropped composition brings us uncomfortably close to Lucretia’s final moments. The heroine’s parted lips and furrowed brow convey her sense of anguish and determination. Artemisia presents Lucretia not as a victim, but as a woman purposefully in charge of her own destiny.

In the Apocryphal Book of Esther the recently married Jewish heroine Esther comes before her husband Ahasuerus, King of Persia, to entreat him to repeal a ruling that all Jews living in Persia should be massacred. Appearing before the king without being summoned was punishable by death and Esther, having fasted for three days and considerably weakened, fainted in his presence. Instead of being punished, Esther was successful in overturning the decree and thus came to be viewed as a symbol of female courage. In this, among the artist’s most ambitious compositions, Artemisia depicts the narrative’s climactic moment.