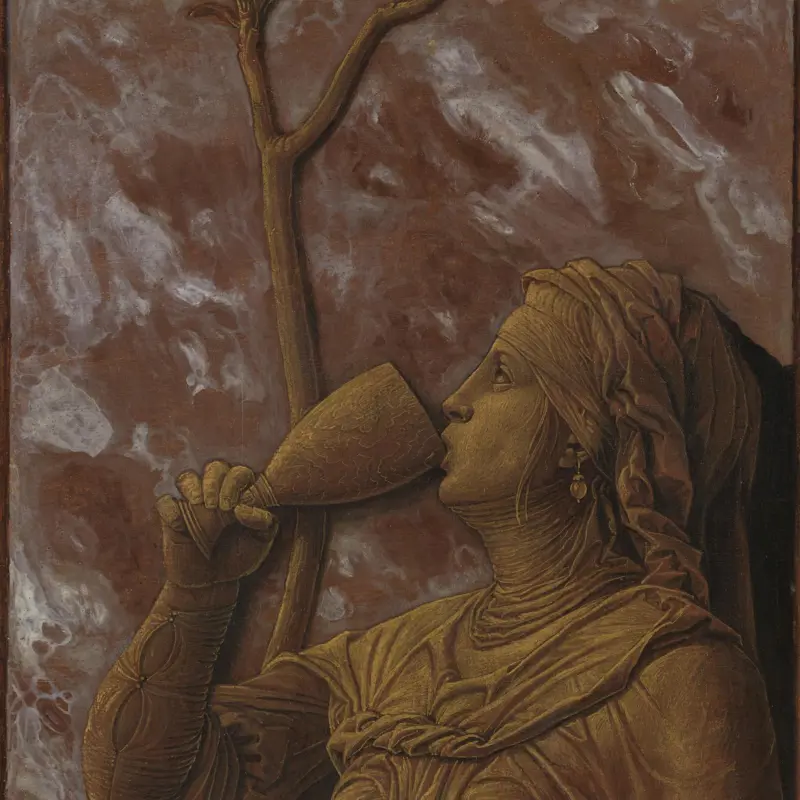

Andrea Mantegna, 'A Woman Drinking', about 1495-1506

About the work

Overview

This woman is most likely Sophonisba, an ill-fated but brave Carthaginian princess; she drains a glass of poison. In 206 BC Massinia allied with the Roman general Scipio to defeat the western Numidians, ruled by Sophonisba’s first husband, Syphax. Massinia fell in love with Sophonisba, but could not dissuade Scipio from his plan to parade her in Rome as a victory trophy. To spare her this humiliation, Massinia sent her poison.

Sophonisba appears as if lit by a strong light coming from the left. Areas hit by this imaginary light – the tips of the folds of the drapery, for example – are bright, while the creases are much darker. The sharp contrasts help create the illusion that the figure is sculpted. Mantegna is showing off: with paint alone he could create a figure that looks as hard and solid as a bronze relief. It may have been made to decorate the studiolo (study) of Mantegna’s patron Isabella d'Este.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- A Woman Drinking

- Artist

- Andrea Mantegna

- Artist dates

- about 1431 - 1506

- Part of the series

- Two Exemplary Women of Antiquity

- Date made

- about 1495-1506

- Medium and support

- egg tempera on wood

- Dimensions

- 71.2 × 19.8 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1882

- Inventory number

- NG1125.2

- Location

- Room 14

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Frame

- 15th-century Italian Frame

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Martin Davies, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools’, London 1986; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

2018Mantegna and BelliniThe National Gallery (London)1 October 2018 - 27 January 2019

Bibliography

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2024C. Elam and G. Rebecchini, Mantegna: The Triumphs of Caesar, London 2024

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the series: Two Exemplary Women of Antiquity

Overview

Viewed from a distance these two small pictures look like little bronze sculptures set against a pink and white marble background. They were known as bronzi finti – fictive bronzes. Mantegna painted several images mimicking antique sculpture, reflecting his interest in the art of antiquity but also showing off his ability to rival the work of sculptors using just paint.

The woman holding the sieve represents Tuccia, a renowned Vestal Virgin (a priestess who maintained the eternal fire at the temple of the chaste goddess Vesta in Rome). The woman with a goblet could be Sophonisba, a Carthaginian ruler who drank poison rather than be taken into slavery by the Roman general Scipio Africanus. Both were celebrated in the work of the fourteenth-century Italian poet Petrarch.

Archaeological discoveries of ancient artefacts sparked new appreciation of the classical world among the aristocracy. Mantegna’s inventive imitation of classical-style artefacts would have appealed to his sophisticated patrons – the ruling Gonzaga family – in Mantua.