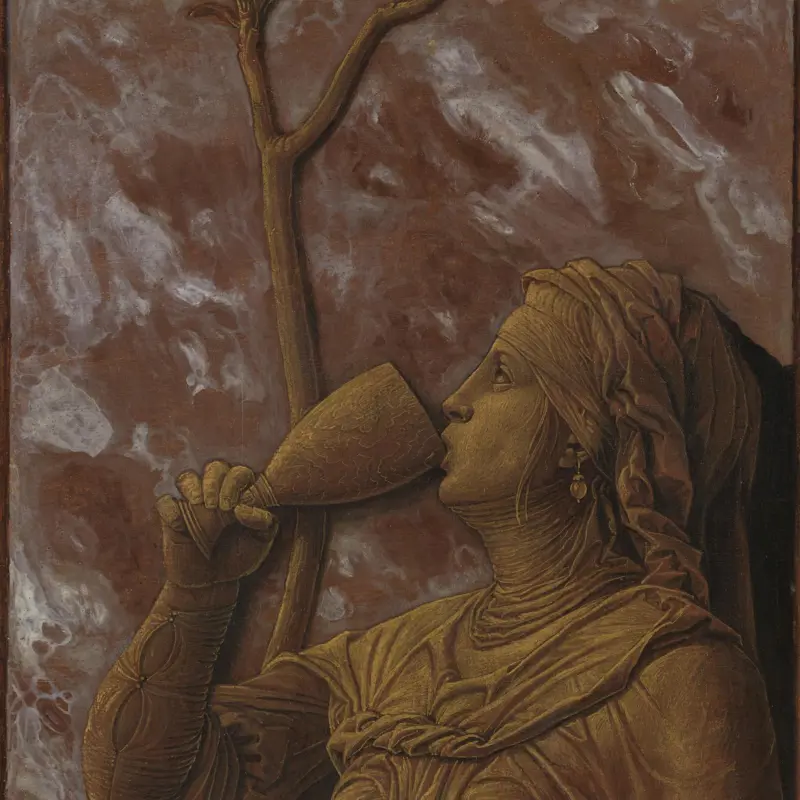

Imitator of Andrea Mantegna, 'Noli me Tangere', perhaps 1460-1550

About the work

Overview

According to the Gospel of John, Mary Magdalene wept when she saw that the tomb in which Christ had been buried was empty. A man appeared and asked her why she was crying – she eventually recognised him as Christ, and reached out to touch him. He stopped her: ‘Touch me not; for I am not yet ascended to my Father’. Noli me tangere is Latin for ‘Do not touch me’.

A vine, rich with grapes, encircles the pruned branches of a large tree, creating an elaborate arch that frames Christ’s slender figure. The grapes symbolise the wine – thought to transform into Christ’s blood – drunk by Christians at Mass in memory of Christ’s death and resurrection.

This panel is one of a group of three resurrection scenes, all in our collection, painted by an artist in imitation of Mantegna’s style.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- Noli me Tangere

- Artist

- Imitator of Andrea Mantegna

- Artist dates

- About 1431 - 1506

- Part of the series

- Three Scenes of the Passion of Christ

- Date made

- Perhaps 1460-1550

- Medium and support

- Oil on wood

- Dimensions

- 42.5 × 31.1 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1860

- Inventory number

- NG639

- Location

- Not on display

- Collection

- Main Collection

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Martin Davies, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools’, London 1986; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

2008Mantegna, 1431-1506Musée du Louvre26 September 2008 - 5 January 2009

Bibliography

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the series: Three Scenes of the Passion of Christ

Overview

These three panels celebrate Christ’s bodily resurrection from the dead. It is likely that all three came from the same series and were painted by the same artist. The pictures reflect aspects of Mantegna’s style, particularly engravings he made at the end of the 1450s and beginning of the 1460s. The jagged rock formations, the angular folds of the draperies and the sinuous figures are particularly characteristic of Mantegna’s paintings.

The painter is unknown but technical analysis of the pigments used shows that they are unlikely to have been painted more than about 50 years after Mantegna’s death. Analysis of the underdrawing (the initial design as drawn on the panel) shows that the painter did not make any alterations to the overall design or any of the details. This suggests that they were tracing directly from a pre-existing image rather than inventing an original composition.