Carlo Crivelli, 'Saint Jerome', about 1476

About the work

Overview

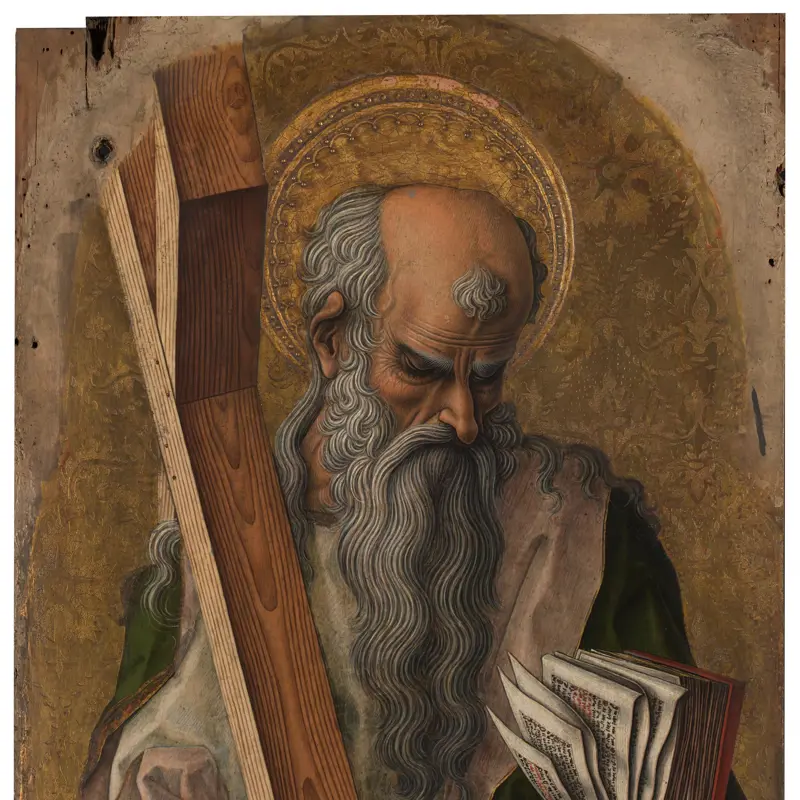

This bearded cardinal once stood at the left side of a small altarpiece that Crivelli painted for a side chapel in the church of San Domenico, in Ascoli Piceno in the Italian Marche. This is Saint Jerome, one of the Fathers of the Church and a favourite saint of the Dominican Order as a defender of the Catholic faith against heresy.

He is lost in contemplation, gazing down at the small brick church he holds in his left hand. In his right hand he holds a bound book of the Bible, which he had translated into Latin; golden rays emanating from the church’s door and window stand for the light his works cast on Church doctrine. At his feet, a tame lion sits on the edge of his robes, gazing up in trusting expectation and raising its paw, which is pierced by a long thorn; Jerome was supposed to have removed it.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- Saint Jerome

- Artist

- Carlo Crivelli

- Artist dates

- About 1430/5 - about 1494

- Part of the series

- Four Panels from an Altarpiece, Ascoli Piceno

- Date made

- About 1476

- Medium and support

- Egg tempera on wood (poplar, identified)

- Dimensions

- 91 × 26 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1868

- Inventory number

- NG788.10

- Location

- Not on display

- Collection

- Main Collection

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Martin Davies, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools’, London 1986; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Bibliography

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the series: Four Panels from an Altarpiece, Ascoli Piceno

Overview

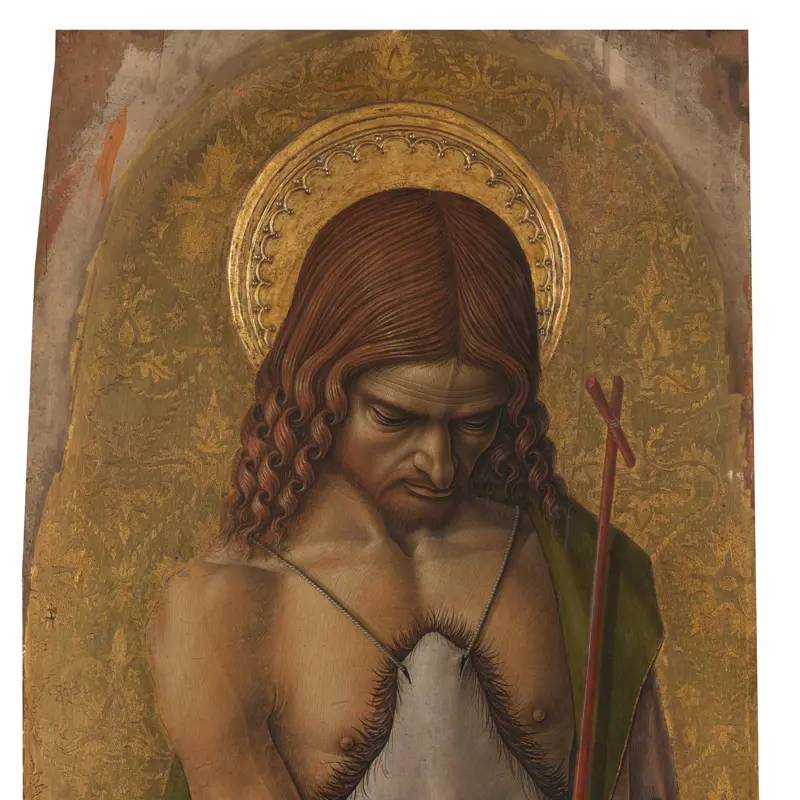

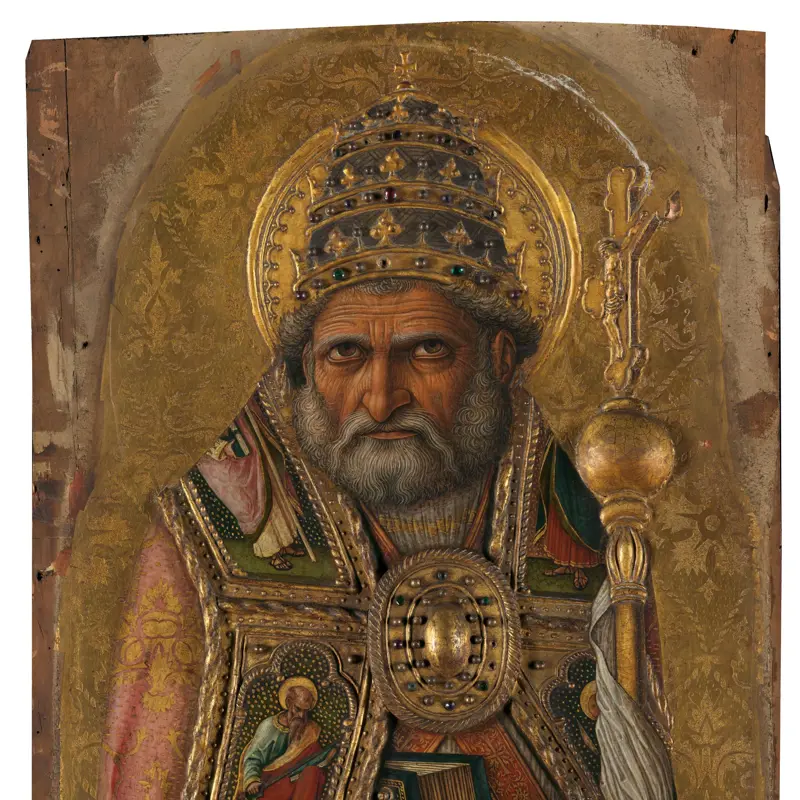

These panels came from an altarpiece which Crivelli painted for a side chapel in the Dominican church at Ascoli Piceno, in the Italian Marche. The saints are identifiable by their attributes: Saint Michael, Prince of Archangels, fighting the devil; Saint Jerome, one of the Doctors of the Church, with his tame lion; Saint Peter Martyr, the second saint of the Dominican Order, a knife buried in his skull; and Saint Lucy, with her eyes on a wooden dish. The choice of saints must have had a special meaning to the original patron.

Although we don’t know who commissioned this polyptych (multi-panelled altarpiece), plainly no expense was spared. The saints’ haloes and damask backgrounds would have sparkled and flickered in the candlelight of the Middle Ages, and lit the church with a glittering golden glow.